Top Story: Public Safety

From the ashes, monumental memories

November 20, 2012

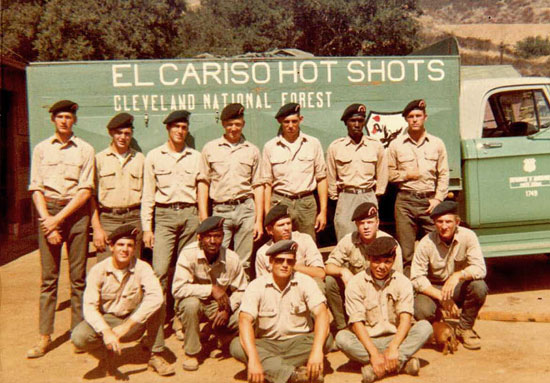

Rich Leak, in front with sunglasses, in the year of the Loop Fire. Five fellow "Hotshots" in this picture died.

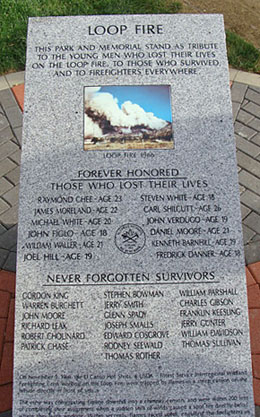

Last week, a memorial was relocated in the San Fernando Valley, a bit of granite that was moved for improvements at El Cariso Community Regional Park. The marker is modest, standing in sharp contrast to the tragedy it commemorates: Forty-six years ago this month, 31 young men were dispatched to a wildfire near Sylmar, and only 19 of them survived.

Rich Leak was 19 that summer, the gung-ho son of a Camp Pendleton fire captain. “All my life,” he recalls “I had wanted to be a fireman.” After attending a summer firefighting program at the U.S. Marine base, he had joined an elite ground crew of “hotshots” based near Lake Elsinore, so called because they were dispatched to the hottest parts of forest blazes. By 1966, his second year with the El Cariso Hotshots, he was a crew foreman, traveling the West to cut fire lines and clear brush around raging wildfires and “loving the excitement and the adrenalin rush.”

The Nov. 1, 1966, call came on a hot day at the end of a long fire season: A faulty power line had sparked a brushfire near Pacoima Dam. Whipped by Santa Ana winds, the blaze had charred some 2,000 acres around Loop Canyon. But it appeared to be dying by the time Leak and his fellow hotshots got what they regarded as an easy assignment—to scrape a fire line along a ravine near the smoldering fire.

“There wasn’t a lot of brush, and the fire was starting to lay down, so the line we were cutting didn’t have to be that big,” Leak remembers. The young men worked without gloves, their hands thick and calloused, their shirtsleeves rolled up. Their orange fire shirts had been washed so many times that they had long since lost their fire retardant coating. No one carried a radio or stood lookout. No one bothered to haul in a portable fire shelter.

And no one understood the dangers of the terrain, Leak says. Now firefighters know that a steep crease in a slope can act as a draft for combustible gasses. But on that day, no one knew that the 31 guys in orange hardhats were entering a death trap. They were nearly done with their work when, at 3:35 p.m., the wind abruptly shifted. A spot fire ignited on the hillside below them. As Leak looked up, the air around him suddenly went wavy.

Down the line an order came: Get out—now! But within seconds, a mighty rush of super-hot gas swept up the 2,200-foot ravine and exploded.

“It was like when you pour lighter fluid on a charcoal barbeque and put a match to it,” Leak remembers. “There was this big wooooof! And then all I could see was just a wall of orange flame. I had to look straight up to see blue sky.”

Leak held his breath so his lungs wouldn’t sear in the 2,500-degree heat, falling to his knees as the shock wave hit him. “Guys were yelling and screaming and praying and calling for their mothers,” he remembers. “I was talking to my Savior, that’s for sure.”

The Loop Fire would change safety protocols for fighting fires in narrow canyons, encouraging lookouts and radios and the development of much-improved fire gear, but not before it claimed the lives of 12 hotshots, most in their late teens and early 20s. Ten more were critically burned and scarred for life by the disaster. The fireball lasted no longer than 60 seconds, but in that time Leak suffered full-circumference burns from his elbows to his wrists, and lost four of his fingers.

After the smoke cleared, he recalls, “I was in shock, running around from one guy to the next, trying to put out the fire with my bare hands. At one point, I looked down at my arms and saw skin hanging down. All I thought was, ‘Wow, I guess I got burned pretty good.’”

It took three years and more than 30 surgeries for doctors to repair Leak’s wounds, using skin grafts from his stomach to repair his damaged hands. He has had to relearn how to type and eat with utensils. He struggles to pick up coins and he has to use both hands to screw a hose onto a faucet. He has no fingerprints.

“For a long time, I was very self-conscious,” he remembers. He went back to school at Palomar College near his hometown of Vista, earning an associate degree in business, thinking he might become a CPA. Then he heard the Vista Fire Department was hiring dispatchers. “It’s hard to describe unless you’re a firefighter,” he says. “It never goes away for me.”

He spent 30 years with the Vista Fire Department, working his way up to fire investigator before retiring to Hesperia 12 years ago. He married a friend’s neighbor and helped raise her two children. “To her, it was what was in my heart that mattered,” he says. “She told me she didn’t even notice I was burned at first.”

Then in 1996, the U.S. Forest Service sent him a notification: A memorial commemorating the 30th anniversary of the Loop Fire was going to be installed in El Cariso Park. Not all the survivors could make it, but some did. Sadly, they recalled the fallen.

“I still remember ‘em,” Leak says. “Raymond Chee, my crew boss, a Navajo I think from New Mexico—very quiet guy, used a brush hook. He was the best hook I’ve ever seen. The White brothers, Michael and Stephen, 22 and 18. They were from San Diego. Their dad was a captain in the Navy. It was devastating for their family.

“John Figlo, he was 18, kind of a quiet guy. Strong. James Moreland. He was in his twenties. Frederick Danner, a tall guy and a really good worker. He died in the hospital. Kenneth Barnhill, nice guy. I knew his brother. Carl Shilcutt, he was 26, one of the older guys on the crew.” He continues down the list: Daniel Moore, Joel Hill, William Waller. John Verdugo, a 19-year-old kid whose body was the first one he saw when he opened his eyes.

Leak kept in touch with the other survivors. He and another ex-hotshot, Ed Cosgrove, began giving talks together to fire academy classes. There were reunions—that’s how he found out that the 1996 marker was in serious need of repair. A drunk driver had hit it and cracked the granite. Skateboarders had worn down the lettering; taggers had marred it with graffiti.

So Leak spearheaded a move for a new one, only to learn that it was going to be moved anyway to make way for park improvements. Last week, a new marker was re-dedicated near a park office building. “It’s near a walkway,” he says. “Granite, just like the original.”

“There are times when I think, ‘What if I’d perished?’” says Leak, now 65. “But you can’t let things haunt you. You have to get over your injuries and go for it. I’m thankful to be here, living my life.”

Posted 11/7/12

Supes step up sheriff scrutiny

October 18, 2012

Confronted with a scathing report on brutality and mismanagement in the Los Angeles County jails, Sheriff Lee Baca has repeatedly insisted that he’s committed to implementing scores of recommended reforms. But given the beating the sheriff himself took in the report, the Board of Supervisors isn’t taking any chances.

The board unanimously voted this week to hire a monitor to track implementation of more than 60 recommendations made by the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence after a year-long investigation. While some of those recommendations address narrow but important policy issues, others urge a major overhaul of the department’s structure and accountability, including creation of an independent Office of Inspector General. The supervisors also voted to require the sheriff to provide progress reports during monthly appearances before the board.

The supervisors’ stepped-up scrutiny—which Baca on Tuesday told the board he supports—reflects their determination to build on the momentum of the jail commission’s widely-praised work and avoid criticism down the road that county leaders again neglected to act.

In its final report, the jail panel accused Baca and other top department officials of failing to rein in violent deputies, despite years of warnings and recommendations from various civilian watchdogs concerned about the treatment of inmates and the county’s potential liability. One of those monitors, Special Counsel Merrick J. Bobb, has written 31 semi-annual reports since serving on the landmark Kolts Commission, which, in 1992, advocated numerous reforms to curb widespread excessive force.

The jail panel noted that many of Bobb’s roughly 100 recommendations involving use of force and personnel issues in the jails went “unheeded” or “languished for more than a decade before the department responded.” The commissioners said concerns voiced by another monitor, the Office of Independent Review, also went unaddressed for years.

“At a fundamental level, the failure to heed recommendations made—and advanced repeatedly over time—is a failure of leadership in the department,” the seven-member commission wrote. “As the sheriff has acknowledged, it was his responsibility to ensure that reforms recommended by these oversight and advocacy groups were implemented and that problems of excessive force in the county jails were addressed. Yet, his response has been insufficient.”

Passages like those prompted the Board of Supervisors this week to intensify its involvement in the implementation of the latest recommendations. The “sheriff alone cannot restore long term-integrity to the department and fidelity to its core values,” Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas said in his motion to hire an “implementation monitor.”

But, as Special Counsel Bobb knows better than most, there’s actually little anyone can do to impose changes on the Sheriff’s Department unless the sheriff himself agrees to them. Unlike the Los Angeles Police Department’s chief, who is appointed by the mayor and reports to a civilian commission, the sheriff is publicly elected. As a result, he has wide legal authority over his department.

“There is no entity, person or institution who can direct the sheriff to do something,” Bobb says. “It is up to the unfettered discretion of the sheriff.”

That’s not to say that the five members of the Board of Supervisors are without leverage; they hold the department’s purse strings, a powerful incentive for the sheriff to be accommodating. The board members also can use their high-profile positions to exert public pressure on the sheriff.

Bobb says it’s been “terribly frustrating” over the years to see his recommendations for departmental change get so little action beyond what the jail commission described in its report as “lip service.” But Bobb says he’s heartened by the department’s movement toward adopting several of his recommendations during the past year as “tremendous pressure mounted on the sheriff and the supervisors to react and respond.”

Perhaps most crucial—and challenging—for the Board of Supervisors is the jail commission’s call for the creation of an inspector general’s office, which would assume responsibilities of the three existing Sheriff’s Department monitors. Those include Bobb’s modest operation, as well as the offices of Independent Review and Ombudsman. The jail commission concluded that this multi-agency approach has been “undermined by the lack of an overarching, consolidated strategy that marshals and leverages their collective strengths.”

The commission stressed that, to be effective, the inspector general must report directly to the board—a point Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky made clear during Baca’s testimony at the supervisors’ Tuesday meeting. When Baca said he’d be “open to a collaborative selection process” of the inspector general, Yaroslavsky cut him short.

“Stop right there,” Yaroslavsky said. “You’re not going to select the inspector general…The Board of Supervisors is going to select the inspector general.”

“Fine with me,” the sheriff quickly responded.

Still, Yaroslavsky did acknowledge the realities of keeping tabs on an agency whose top official is elected by the public. The creation of an inspector general, the supervisor said, requires the sheriff’s cooperation. “He can’t inspect what he can’t see.”

Baca assured the board that the department has not withheld information from monitors in the past and won’t be doing so in the future. The Board of Supervisors, he said, “will decide what priorities you want this person to fulfill, and those priorities will be honored.”

Sheriff watchdogs: Special Counsel Merrick Bobb, left, and Michael Gennaco of the Office of Independent Review.

Posted 10/18/12

The big inmate shift: one year later

October 12, 2012

Appointed last October, Probation Chief Jerry Powers promptly became responsible for realignment's rollout.

Don’t expect a lot of folks in Los Angeles government to be toasting Sacramento in celebration of this month’s one-year anniversary of the most dramatic remake ever of California’s criminal justice system. Called “realignment,” it triggered a massive overnight transfer from the state to its counties of responsibility for supervising certain ex-prisoners and jailing a new, more serious class of offender.

The changes were pushed by the governor and legislature despite strong resistance from local authorities, who argued that the plan was being rushed to relieve the state of its prison crowding and budget problems at the expense of public safety and the dwindling resources of local governments.

Now, data collected by Los Angeles County suggests that the impact here is even more challenging than anyone envisioned, prompting a scramble for new solutions and dollars.

County officials say, for example, that they received more “high risk” former state inmates to supervise than they’d initially predicted, and many arrived with mental illnesses that were far more serious than expected. Those individuals have been placed in costly lock-down psychiatric facilities, leap-frogging other patients who’ve been bumped to waiting lists and, as a result, are consuming precious beds in public hospitals.

Meanwhile, more than 30% of the 11,000 former state inmates whose supervision has been transferred to the county’s Probation Department were rearrested during the past year for allegedly committing crimes ranging from vehicle code violations to serious felonies, including 16 murders, 23 attempted murders and 205 robberies. County officials emphasize, however, that these same alleged offenses could just as easily have occurred had state parole officers remained responsible for post-release supervision.

And it doesn’t end there. County probation Chief Jerry Powers says another provision of the realignment law, AB 109, carries the potential of even more problems, placing new strains on the county’s already bursting jail system and raising more questions about risks to the public.

Under AB 109, the county is now responsible for jailing criminals convicted of non-serious, non-violent, non-sexual crimes—offenders, who, in the past, would have been sentenced to state prison and placed on parole after their release. But under the realignment law, there’s no requirement—or funding source—for them to have any supervision, or “tail,” at all after their release from county jail.

“Frankly,” Powers told the Board of Supervisors this week, “that scares me more than this population that is coming from the state prison system [for county supervision.]”

The news, however, is not all grim.

Reaver Bingham, the point man for realignment in the county’s Probation Department, says his agency has, among other things, begun to beef up supervision ratios because of the unexpected number of ex-state inmates who are considered to be higher risks to commit new crimes. “If they mess up,” he says, “we’re right there to address the violation.”

He also said that 90% of the former state prisoners who’ve been ordered since last October to report to the county had done so, allowing authorities to create customized supervision and treatment plans for them. Of those who failed to show, Bingham says, warrants were issued and most of the missing individuals were contacted or picked up within 30 days. As of this week, he says, there are 917 active warrants, not counting the 529 warrants issued for individuals who’ve now been deported. Bingham acknowledged that some of the county’s new charges have been arrested for new crimes—some of them serious—but he says most are property- and drug-related offenses. More than 600 cases, for example, were for methamphetamine possession, while nearly 400 involved arrests for burglary, according to Sheriff’s Department records.

Bingham says the recidivism among the group is not surprising. Although these ex-inmates were transferred from the state after completing sentences for non-violent, non-serious, non-sexual offenses, they often have earlier, more egregious convictions. “I think it’s safe to say that over 50% have serious and violent crimes in their past,” says Bingham, a 30-year veteran of the probation department.

Like his boss, Powers, Bingham says he’s also concerned about the lack of post-release supervision for inmates who, for the first time, will be serving sentences in county jail rather than in state institutions. So far, the average jail stay for these individuals is 12 months, excluding time already spent in custody and automatic reductions in sentences.

“When they’re out, they’re done,” Bingham says. In the past, when this same class of inmate was released from state prison, they’d receive years of parole supervision, giving California authorities leverage to try to avert bad behavior and reduce recidivism. “Without supervision, we have no opportunity to determine whether these people have benefited from programs they’ve received during incarceration with us,” Bingham says. “We have no idea whether the rehabilitation took to them.”

Law enforcement authorities throughout California have been pushing for legislation that, at a minimum, would attach a “search and seizure” requirement to the release of inmates from county facilities, just as the state has been doing for the same class of prisoner. This would give authorities the right to search a person and his property. Any violations could lead to the filing of new charges.

“At least that way, the system is still in their life,” says Mark Delgado, executive director of the Countywide Criminal Justice Coordinating Committee, which has played a key role in the realignment process here.

From the start, one of the most difficult populations to address in realignment has been those inmates with mental health needs. Initially—until the intervention of the governor’s office—county officials couldn’t even get complete medical histories of these individuals from the state to create treatment programs.

Dr. Marvin Southard, director of the county’s Department of Mental Health, says some of these ex-inmates have “garden variety mental illnesses,” for which about half are engaged in treatment. “The challenge has been that there’s a second minority group with very severe mental illnesses.”

These people, Southard says, have been immediately placed in secure, privately-owned psychiatric facilities with which the county has contracts. “Any one of those cases could have been problematic for individual and public safety,” Southard says.

But, according to Southard, there’s been a price to pay—both in dollars and in the operation of the mental health system. These AB 109 clients, he says, “have jumped the line,” creating a backlog among patients in serious need of those same beds. “This has put more pressure on the psych wards at the county hospitals. It backs up the system.”

Still, Southard, Delgado, Bingham and others say there has been a bright spot in all of this: realignment has forced an unprecedented level of cooperation among agencies throughout the county.

Just last week, for example, the Department of Mental Health, the Sheriff’s Department and the Department of Public Health teamed up to begin providing the new AB109 inmates in county jail with a promising anti-addiction drug called Vivitrol.

“We’re working together more synergistically now than we ever have,” says Bingham, who credits his staff with helping make interagency strides.

“Whether you agree with realignment or not,” adds Delgado, “everyone has pulled together, committed resources and been fully invested in doing whatever they can to make this thing work.”

Posted 10/12/12

Sheriff agrees to broad jail reforms

October 3, 2012

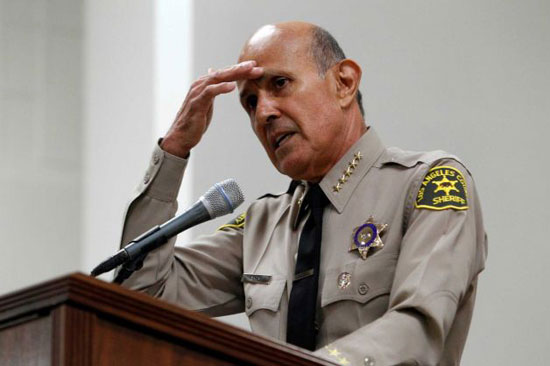

Breaking a nearly week-long silence, Sheriff Lee Baca says he applauds the commission's efforts. Photo/AP

Chastened and conciliatory, Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca said Wednesday that he fully agrees with—and will begin implementing—dozens of recommendations from a blue-ribbon panel that accused him and his top command of failures in leadership that fostered a culture of brutality among jail deputies.

“I couldn’t have written them better myself,” Baca said of the more than 60 recommendations issued last week by the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence, which concluded a year-long investigation with a blistering report on management breakdowns inside the nation’s largest jail system.

But, in response to a question during a packed news conference, the elected sheriff brushed aside talk of a possible resignation. “I’m not a person who thinks about quitting on anything,” he said.

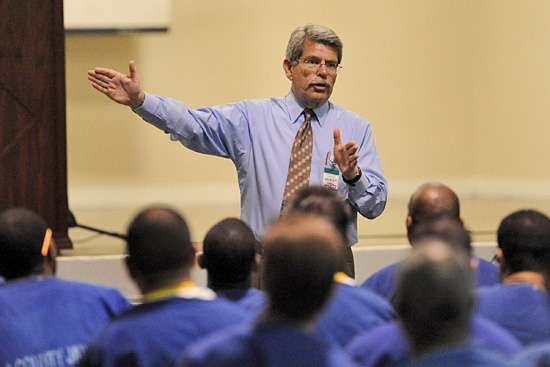

Baca convened the massive media gathering in the chapel of the Men’s Central Jail, an aging facility on the edge of downtown Los Angeles, where the vast majority of brutality allegations against deputies have been leveled over the years by inmates and civilian monitors, including the ACLU. As Baca spoke from the pulpit under a large cross, more than 20 members of his jail command staff sat solemnly behind him, some on risers. In the pews—behind a bank of TV cameras—were rows of inmates, dressed in L.A. County’s jailhouse blues.

It was an usually theatrical setting for the sheriff’s first response to the 194-page report by the jail commission, which was appointed by the Board of Supervisors and included former judges, a police chief and a longtime South Los Angeles pastor. And he went to great lengths not to criticize any aspect of the commission’s effort, which he said he supported from the outset. “I’m paid to take criticism,” said the sheriff, dressed in uniform. “Even when it’s unfair.”

In fact, as he has in the past, Baca was quick to accept blame for use of force issues that had been intensifying for several years. Those problems became especially acute under the leadership of Undersheriff Paul Tanaka, according to the commission. The panelists concluded that Tanaka had “exacerbated” the problems by, among other things, publicly belittling internal affairs investigators and unilaterally killing a plan to break-up deputy cliques by rotating them into new jail assignments.

“They needed me to set a higher standard for performance,” Baca said of Tanaka and other key members of his command staff, whom the sheriff said had failed to alert him to the brewing problems inside the crowded county lockup.

The commission was highly critical of Baca for not holding Tanaka and others accountable for their conduct, saying his failure to act has sent a troublesome message to the rank and file. Repeatedly pressed on that point by reporters on Thursday, the sheriff sharpened his tone. “I’m not a person who acts impulsively or in my own self interest when it comes to someone else’s career. We will either have the facts or we won’t have the facts.”

Baca, who said he is reviewing Tanaka’s conduct, added: “I don’t lead with my ego. I lead with my intellect.”

The sheriff said Tanaka, a certified public accountant who was not at Wednesday’s event, would remain with the department, overseeing administrative services and the agency’s budget, a far smaller portfolio than he once held.

Among the commission recommendations (read the panel’s executive summary here), Baca said he supports two that, in concept, would vastly enhance oversight of the jail operation.

One would create an independent Office of Inspector General reporting to the Board of Supervisors. The new agency would essentially consolidate and broaden the review responsibilities of three existing civilian bodies—the Special Counsel, Office of Independent Review and the Office of the Ombudsman. The idea for an inspector general is modeled after a watchdog agency that oversees the Los Angeles Police Department. Exactly how such a body would be created and function for the Sheriff’s Department will likely be a matter of considerable public debate.

The second recommended reform would be the creation of a new assistant sheriff position, staffed by an experienced corrections leader from outside the department. This person would report directly to Baca, who said he supports the idea and already is seeking candidates.

The commission also called for tougher discipline for excessive force and dishonesty, a simplification of the disciplinary system and creation of a new investigations division that would report directly to the sheriff.

Baca said he welcomes these recommendations as a way to make “a stronger and safer jail,” a place where deputies respect the humanity of inmates, who, for their part, can learn life skills and end the cycle of recidivism. “I do have some deputies who have done some terrible things,” he said.

Still, Baca stressed that since last October when the ACLU presented him with numerous accusations of excessive force in the jail, he aggressively instituted a series of measures that have reduced “significant force” in the jails by 53 percent—“a historic low,” he said. He said he also has initiated tough new policies while increasing supervision, video surveillance and training. Baca said he and his management team have “responded massively.” (A video of Baca’s hour-long news conference can be seen here.)

In its report, the jail commission acknowledged the significant improvements Baca had brought to the custody operation after he belatedly became engaged with the issues. But commission member Robert Bonner, a former federal judge and ex-head of the Drug Enforcement Administration, said those measures do not go far enough and that the department needs sweeping cultural and structural changes.

“The modest steps taken by the sheriff are not permanent, institutional reforms,” Bonner said during last week’s commission meeting. “They are Band-Aids—meant to staunch the bleeding.”

Posted 10/3/12

A harsh verdict on jails

September 28, 2012

Commission Chair Lourdes Baird says it's now up to the supervisors and sheriff to enact proposed reforms.

After nearly a year of investigation, the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence released its final report on Friday, concluding that comprehensive reforms are needed throughout the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department because Sheriff Lee Baca and some of his top managers failed to confront persistent deputy brutality behind the bars.

“The commission heard repeated and consistent accounts of leadership failings in the department over a period of years,” the seven-member panel wrote. “Thus, it is not surprising that supervisors struggled to control deputy insubordination, inappropriate treatment of inmates, and aggressive conduct both on and off duty by deputies working in Custody.”

(Read the executive summary and entire report.)

The commission, which was appointed last October by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, was unsparing in its criticism of Baca and his second-in-command, Paul Tanaka.

“Both Sheriff Baca and Undersheriff Tanaka have, in different ways, enabled or failed to remediate overly aggressive deputy behavior as well as lax and untimely discipline of deputy misconduct in the jails for too long.”

What’s more, according to the report, Baca failed to hold Tanaka and other senior leaders accountable for serious lapses in conduct and judgment, “thereby sending a troubling message to a department in need of a clear directive that accountability is expected and will be enforced at all levels.”

During the commission’s Friday meeting at the downtown Hall of Administration, the strongest rebuke of Baca among the panelists came from retired federal judge Robert Bonner.

“The fact is that the sheriff is not someone as a manager who wanted to hear about problems,” Bonner said. “He seems to have had his head in the sand, dealing with other problems, ones that perhaps interested him more—but not minding the store when it came to running the jail in accordance with lawful and sound use of force policies.”

In all, Bonner and his colleagues issued more than 60 recommendations aimed at improving training and accountability within the nation’s largest local jail system. Most significantly, the commissioners called for the creation of an Office of Inspector General, which would essentially consolidate the responsibilities of existing oversight bodies “who suffer from too many gaps among them to effectuate comprehensive and lasting changes in the Department.”

“Too often, the department has paid lip-service to recommendations of these oversight bodies knowing that there has not been sustained follow-up to ensure their recommendations are carried out.”

The proposed Inspector General’s office would report directly to the Board of Supervisors and would operate—in name and function—similarly to the agency that oversees sensitive issues within the Los Angeles Police Department. It reports to the civilian Police Commission.

To enhance accountability within custody facilities, the jail commission also recommended the creation of a new position—assistant sheriff for custody—that would be staffed by “a professional and experienced corrections leader,” presumably someone outside the existing chain of command.

The commission further called for tougher discipline for excessive force and dishonesty, a simplification of the disciplinary system and the creation of a new investigations division within the department that would report directly to a chief.

Ultimately, it is the publicly elected sheriff who’ll decide whether many of the proposals for internal reform will be implemented. Baca, confronted with a cresting controversy over jail violence last year, initiated a series of measures that have significantly reduced the use of excessive force. The commission acknowledged Baca’s efforts but also took a swipe: “Simply stated, the Sheriff did not pay enough attention to the jails until external events forced him to do so.”

Many of the sharply-worded findings in the jail commission’s report were revealed three weeks ago in a series of presentations by the commission’s volunteer staff of lawyers, some of whom are former federal prosecutors and had served on other police reform bodies, including the Christopher Commission, which was created after the 1991 LAPD beating of the late Rodney G. King.

The lawyers reviewed thousands of documents and interviewed more than 150 witnesses, including current and former members of the Sheriff’s Department. Some of those witnesses testified publicly that Tanaka and his hand-picked subordinates had consistently frustrated their efforts to crackdown on violent deputies.

“Not only did he fail to identify and correct problems,” the commissioners concluded, “he exacerbated them.”

The report also criticized Tanaka for helping to create a perception of “patronage and favoritism in promotion and assignment decisions” in the department.

Tanaka, who’s an elected official in Gardena in addition to his sheriff’s department job, has accepted $108,311 in campaign contributions from 336 Sheriff’s Department employees from 1998-2011, the report said.

“There is a perception among rank-and-file employees that contributing to Tanaka’s campaigns is important to promotional and assignment decisions,” the report said, pointing out that in a few of the races Tanaka was running unopposed and that “numerous LASD contributors did not live in the City of Gardena.”

“Concerns were expressed by employees at almost every level of the department,” the report continued. “Even employees who did not contribute felt pressure to attend campaign events in order to have ‘face time’ with the Undersheriff.”

Tanaka is not alone in accepting campaign contributions from the sheriff’s staff, the report said, noting that Baca also has received at least $97,850 from department staff between 1999 and 2011. However, those contributions made up just 7% of Baca’s overall contributions, whereas staff contributions accounted for about 30% of the campaign funds raised by Tanaka.

The commission noted that there is no formal sheriff’s department policy on accepting campaign donations; Baca has told the commission that he’s in the process of developing one.

Despite the unremittingly grim nature of their findings, the commissioners said they believe their recommendations, if implemented, “can bring about lasting and meaningful changes within the Los Angeles County jails.”

Commissioner Jim McDonnell, the Long Beach police chief, noted in his comments that there has been no great public outcry or groundswell to fix the years of documented problems inside the jails.

“Why is this? The people most directly impacted don’t have a lot of credibility in the eyes of the public, nor does the behavior that got them to county jail generate much in the way of sympathy and support,” he said. “That’s just the reality that we face. That makes the responsibility of this board that much more critical.”

“My concern,” he added, “is that if serious remedial action is not taken immediately, federal authorities may pursue legal action against the county, which would likely result in a consent decree. That would an onerous, labor intensive and very expensive path to reform.”

Posted 9/28/12

Jail probe blasts sheriff’s brass

September 7, 2012

Tamerlin Godley presented findings of the personnel and training portion of the investigation. Bert Deixler, right, discussed the discipline probe.

In a day that will surely be remembered as one of the most difficult in the history of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, the investigative staff of the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence on Friday issued a broad condemnation of the agency’s top management, including Sheriff Lee Baca, for fostering and even encouraging unnecessary violence by custody deputies, while tolerating cliques in their ranks and a code of silence.

Among other things, Baca was criticized for failing “to monitor and proactively control use of force,” turning the responsibility over to top aides “without effective oversight.” One of those aides was Undersheriff Paul Tanaka, the department’s second-in-command, who, according to commission investigators, “discouraged supervisors from investigating deputy misconduct” and undermined the credibility of internal investigators.

Despite concerns expressed by a commander and others about the use of excessive force in the Men’s Central Jail, “key department leaders ignored and failed to address deputy aggression at MCJ,” according to one of six Power Point presentations discussed during a dramatic session of the seven-member Jail Commission, which was created by the Board of Supervisors last October.

Baca, who had earlier said he was unaware of force problems in the jail, strongly backed the panel’s creation and instituted a series of reforms within the department that, by all accounts, have substantially reduced use of force incidents in the dangerous jail system. He also has defended Tanaka, calling him “uniquely qualified.”

The commission’s investigative work was done for free by nearly 50 lawyers from across Los Angeles, some of whom played key roles in earlier law enforcement probes, including the Christopher Commission. They were led by General Counsel Richard Drooyan of Munger, Tolles & Olson. Drooyan, like many of the attorneys he recruited, formerly worked in the U.S. Attorney’s Office.

The findings will be incorporated into a final report with recommendations for reform by the high-profile commissioners, led by Chair Lourdes Baird, a retired federal judge, and Vice Chair Cecil “Chip” Murrary, former pastor of First AME Church. Release of the report is expected late this month.

The findings were divided into six areas of inquiry, included here with links to each of the detailed Power Points. Those areas were: management, use of force, culture, personnel, discipline and oversight.

Some of the findings had been foreshadowed in months of public testimony before the commission from current and retired Sheriff Department employees who said their efforts to crack down on excessive force had been undercut by Tanaka and former Men’s Central Jail Captain Daniel Cruz—both of whom have denied being lax in their responsibilities.

But what was surprising about Friday’s session was the breadth of the alleged failures and the no-holds-barred language used to describe them.

The investigators, for example, said the sheriff “failed to hold senior management accountable,” even though he’s acknowledged publicly that they kept him in the dark about the jail violence problems. Moreover, investigators said Baca has failed to discipline Tanaka, although the sheriff himself has said that his No. 2 had made comments that were “inappropriate and sent the wrong message to department personnel.” There is “no record that senior management has been disciplined, demoted, or faced any consequences,” according to the investigators.

Investigators argued that these lapses at the top helped create a culture in which excessive force against inmates could grow—force that was “disproportionate to the threat posed [to deputies] or when there was no threat at all.”

Some deputies, according to investigators, pitted inmates against each other in violent confrontations and “used humiliation as a tool to harass inmates” through strip searches.

What’s more, according to investigators, the internal review process only encouraged more of the same. They found that, between 2006 and 2011, less than 1% of force incidents were determined by the department to be “unreasonable,” which “casts doubt on the integrity of its force assessments and the reliability of its data.” Only two deputies in the past five years were found to have provided false statements in regard to force reports, a number that raises questions about the adequacy of internal investigations.

Also contributing to the problems, investigators said, were sweeping shortcomings in the areas of personnel and training, including a failure until last year to rotate assignments in the jail. This failure, investigators argued, “contributed to the growth of cliques, a culture of silence and problems of insubordination.” In earlier testimony before the commission, it was disclosed that Tanaka had scuttled one jail captain’s plan to rotate jail assignments, even though it had been approved through the chain of command.

The investigators were also harshly critical of the quality of training and supervision in the jail, saying some of the newest custody deputies have been assigned to the most difficult floors or modules and that the department “fails to adequately monitor” their performance.

Talking truth and power behind bars

August 22, 2012

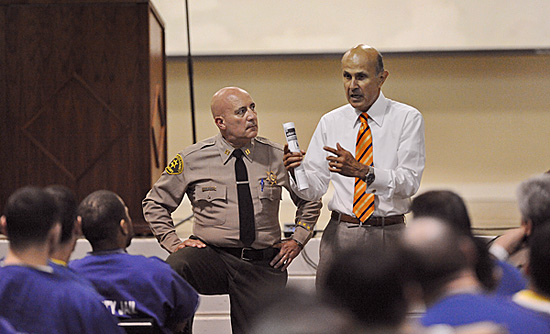

Sheriff Lee Baca, right, and Central Jail Captain Ralph Ornelas hold a "town hall meeting" with inmates.

Lee Baca is standing before a captive audience, sounding more like a preacher than the leader of the nation’s largest sheriff’s department.

“Start decorating your minds like you would a palace,” Baca implores a group of 90 inmates inside the archaic Men’s Central Jail. “Put positive things in there that will make you happy…I happen to believe you’re worth something.”

The men, seated shoulder-to-shoulder on metal pews in a jailhouse chapel, nod in agreement, giving the sheriff an appreciative hand to go along with their list of grievances. Earlier in the session, they’d complained to the boss about broken shower heads, uncomfortably cold air, inadequate “roof-time” recreation and deputies who, for seemingly no good reason, threaten to yank them out of the sheriff’s pet educational program.

Although the incarcerated men expressed gratitude for Baca’s appearance and assurances, the reaction to this “inmate town hall”—and the 173 others that have been convened during the past year—has been far less friendly among the sheriff’s other jail constituency: the deputies who work there.

Their union contends that the town halls have undermined the authority of deputies because inmates are being encouraged to, among other things, sidestep the chain of command, taking their complaints straight to higher-ups. The impact, according to union leaders: a potentially more dangerous workplace as frontline deputies lose the upper hand.

“They’ve never had the sheriff come in and say you can go talk to the captain,” Mark Divis, vice president of the Association of Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs, says of the inmates. “The word from the top is that you can go right past those guys [the deputies] and we’ll come running…At what level do you realize that you’re not dealing with a large number of rational individuals? If you’re in a church, it’s a bad place to talk about Satan worship.”

According to a union survey presented to the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence, 71% of 447 responding deputies said Baca’s town halls had made inmates feel more “empowered” and less respectful. Forty-nine percent said inmates actually had become more hostile toward their jailers.

Baca has dismissed the survey as not fully representative of the roughly 2,000 deputies who serve inside the county’s jails. Still, the findings do suggest a cultural divide that poses a significant challenge for the sheriff as he tries to fix a jail system rocked by allegations of deputy brutality and mismanagement. Among the rank-and-file, Baca’s self-described humanist views are not always embraced.

In police circles nationwide, Baca is known as a fervent reformer who believes in the power of innovative educational programs to transform the lives of inmates and end their cycle of recidivism. He has a doctorate from USC in public administration and says his “second love” is teaching, which he’s done at various levels for more than 30 years.

The inmates he visited last week were part of an educational program that focuses on positive decision-making and self-esteem development. The participants live together in a dorm, not in the packed, dank cells that have drawn most of the scrutiny over deputy conduct.

For that reason, their town hall meeting had a more upbeat tone than most, with some inmates thanking Baca for the opportunity to learn an assortment of life skills for the first time, from job training to anger management. As one told the sheriff: “I’m the kind of guy who ends up in Vegas with three hookers and married to one.”

Baca began the town hall meetings last October as the furor over alleged deputy brutality escalated. Saying his subordinates had failed to inform him of the problems, Baca ordered a series of management and policy changes that have helped reduce incidents of significant force. Baca also backed the creation of the blue-ribbon jail commission by the Board of Supervisors, encouraging current and former members of the department to come forward with testimony critical of top supervisors.

As of late last week, according to Men’s Central Jail Captain Ralph Ornelas, 6,870 inmates had voluntarily attended the town hall meetings, which run about 30 minutes and are led by captains. Baca himself has presided over only a few.

“I’ve learned to listen to what they say,” Ornelas says of the inmate meetings. “Sometimes it has validity. Sometimes they have a certain agenda against a particular deputy.” Whatever the case, Ornelas says, he believes the meetings are valuable because if inmates “see you as a person, then they’re less apt do to do something to you.”

The captain has statistics on his side. The numbers show that not only have use of force incidents declined, so too have inmate assaults on deputies.

The jail commission’s general counsel, Richard Drooyan, says he sees the union’s resistance to the meetings as “a serious issue,” revealing the philosophical and managerial hurdles ahead for Baca.

“My view is that these meetings represent a positive development. They reduce tensions and that reduces violence,” Drooyan says, adding: “You change the culture by making sure supervisors are on board with your vision and that they tell their charges, ‘This is the way it’s going to be and if you don’t do it, you’ll be held accountable.”

Union leaders argue, however, that such views are better suited to the ivory tower than the central jail. The union’s executive director, Steve Remige, says many inmates simply won’t change their stripes no matter how much “the sheriff wants to teach them peace, love and freedom.”

Take, for example, the two inmates he says participated in Baca’s prized educational program, called MERIT—Maximizing Education Reaching Individual Transformation. “Just hours after graduating from MERIT,” Remige says, “they were caught trying to get some exposed metal under some ceiling tiles.” Remige says he assumes they were looking for materials to make jailhouse weapons.

Nonetheless, the problems in the jail have handed Baca a high-profile opportunity to showcase his reformer’s approach to incarceration. To that end, he invited Los Angeles County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky to observe last week’s town hall—and to say a few words at the end to the men participating in Baca’s educational program.

“The sheriff is trying to do something that is not conventional. On your shoulders rests the sustainability of this program,” the supervisor said. “He’s stuck his political reputation on the line by treating you like human beings…Don’t screw it up.”

Posted 8/16/12

Jail panel gets tough

August 9, 2012

Citizens' Commission on Jail Violence members, from left, Lourdes Baird, Robert Bonner and Dickran Tevrizian.

For nearly three hours, members of the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence remained silent as one of the most powerful men in Los Angeles law enforcement defended himself against accusations that he undermined supervision in the county jails and helped create the conditions for a rise in deputy brutality.

Under questioning from one of the blue-ribbon panel’s lawyers, Los Angeles County Undersheriff Paul Tanaka said he and others at the highest levels of the department were “caught by surprise” by the force being used inside Men’s Central Jail. He said lower-ranking supervisors had never alerted them, despite a paper trail of alarming internal reports and contradictory testimony from a former jail commander.

Throughout his morning of long-awaited testimony last week, Tanaka also repeatedly said he could not recall details of key events or conversations, including whether he’d ever talked with the sheriff about use of force issues in the jail. “We may have had discussions,” he said. “I don’t remember.”

When the commission’s lawyer had finished his questioning, it was time for the panel members to weigh in. During hearings over the past several months, their inquiries have mostly been aimed at eliciting more details and context—especially from former and current members of the Sheriff’s Department who’ve testified critically of Tanaka and former jail captain Daniel Cruz.

But this time was different.

This time, with a crowd of uniformed sheriff’s officials in the Board of Supervisors’ hearing room last Friday, several commissioners used their questions to dress down the department and its No. 2 man. Although Sheriff Lee Baca would testify later in the day—admitting that “we screwed up in the past”—he was handled more gently, praised for the aggressive measures he’s taken since last fall to heighten accountability and reduce the use of force in the county’s jam-packed lockup.

Not so with Tanaka, on whom both witnesses and the commission have increasingly focused attention.

“I was astounded when you informed the commission that you were not aware of the magnitude of excessive force issues at Men’s Central Jail,” said Dickran Tevrizian, a former Reagan appointee to the federal bench. “It seems to me that…everybody buried their head in the sand with regard to this issue. So it’s very hard for a rational person to understand this.”

“I can’t argue with you,” said Tanaka, who remained largely conciliatory.

Tevrizian also said that after his appointment to the commission, he’d received numerous anonymous allegations from within the department claiming that favoritism is shown towards those considered to be “one of Tanaka’s guys.”

The undersheriff dismissed that contention. “There are people that maybe don’t get to where they believe they should and I’m an easy target,” he said. “I understand that. It’s my position.”

The Rev. Cecil L “Chip” Murray, former pastor of the First AME Church, asked Tanaka: “I wonder if there is any portion of you that might say on the record: ‘I was not always diligent in my performance and the responsibility rests, to a large extent, on me and with me.’”

Tanaka, who oversaw the custody division as an assistant sheriff between January, 2005, and June, 2007, agreed that if he had been “100 percent diligent and looked into every possible aspect of our operation, we wouldn’t be here today.”

Former California State Supreme Court Judge Carlos R. Moreno said he was particularly concerned by revelations that large numbers of uncompleted use of force reports were stuck in drawers or never forwarded to the command staff. This failure, he said, could mean that a deputy’s personnel history might be worse than represented to plaintiffs during the discovery process in lawsuits.

“Do you have any thoughts about what I would consider to be a fraud having been committed on the courts?” Moreno asked.

Tanaka responded that such lapses, which he said are not occurring today, would be “unacceptable and very disturbing.”

Former U.S. attorney and federal judge Robert C. Bonner, meanwhile, questioned Tanaka about the potential impact of openly stating his dislike for the department’s internal affairs bureau—statements Tanaka insists have been aimed at the bureau’s lengthy and sometimes “less than respectful” investigative process, not its vital function within the department.

“What message is sent when a senior manager of a law enforcement agency like yours belittles I.A. in front of line deputies?” Bonner asked. “Well, it’s the wrong message, isn’t it, Mr. Tanaka?”

“It can certainly be construed as the wrong message, and I hear you loud and clear,” Tanaka responded, adding: “I don’t make it a practice of going around and offering negative comments about the internal affairs bureau today.”

“Well that’s gratifying to hear,” Bonner said.

Some of Bonner’s most detailed and barbed questioning centered on a plan Tanaka spiked in 2006 that would have required deputies to begin rotating between different floors in the Men’s Central Jail in downtown Los Angeles. The jail’s captain at the time, John Clark, was concerned about the formation of deputy cliques and unnecessary use of force. His plan had been approved by the jail commander and the chief of custody operations.

Just days after Clark’s plan was circulated, Tanaka said he was inundated with some 200 e-mails, many of them identical, from deputies complaining that proposed changes were unfair to those “who’ve worked years to obtain a certain spot.” Tanaka told the commission that the letters were “a signal of distress.”

In a controversial move that was the subject of earlier commission testimony, Tanaka met privately with the deputies and told them he was rescinding Captain Clark’s plan. Bonner said this action, taken without consulting Clark, “undercut” and “undermined” a captain attempting to tackle serious problems in the jail.

“I don’t consider anything that I’ve ever done in this role or any other as undermining the command of anybody,” Tanaka said. “The only thing I’ve ever done is in the best interest of this organization.”

But as Bonner noted, Tanaka was not even familiar with details of the plan he dumped. The undersheriff testified that he thought the rotation plan called for a change in shifts, requiring deputies to work new hours, potentially creating problems in their personal lives. Clark’s plan called only for a change in work locations.

“And you were wrong, weren’t you? Because it [the rotation plan] didn’t include shift changes,” Bonner said. “You know that now, don’t you?”

“Based on the written documents,” Tanaka responded, “it certainly contradicts what I remember.”

Baca, during his testimony, came to the defense of his undersheriff, calling him “uniquely qualified for this position.” Baca said that Tanaka’s background as a certified public accountant has helped the department navigate its huge budgetary challenges.

“What’s problematic here is that everyone’s to blame and I’ll take the blame for everyone because of my position as the sheriff,” Baca said, but added: “The chain of command, in many respects, let me down.”

Although the commission’s general counsel, Richard Drooyan, tried to get Baca to describe how he would hold those in his command structure accountable, the sheriff wasn’t biting.

“This commission is a great commission, Mr. Drooyan, but you’re not going to tell me how to discipline my people,” Baca said. “I don’t do that in public and I’m not going to do it now.”

Baca also said he hopes the commission will focus its recommendations on ways to improve the organization. “Let me deal with the some of the souls that you might think are a little off base,” the sheriff said. “I can deal with them.”

The commission, created by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors last October, will convene again on Friday and is expected to issue a final report in September.

Photos by Scott Harms/Los Angeles County

Posted 8/2/12

High season for rescues

July 25, 2012

For the Malibu Search and Rescue team, things can get crazy-busy out there.

Emphasis on the crazy. Inspired by videos posted online, hikers are flocking to spots like Rindge Dam in Malibu Canyon, where the inexperienced, unlucky or foolhardy can get into trouble fast.

A dramatic, 7-hour rescue operation last week—in which three lost and stranded hikers who’d apparently learned of the spot in an Internet video had to be pulled out of a deep canyon in the darkness—illustrates what can happen when YouTube-fueled aspirations run into the rugged realities of the great outdoors.

Other factors attracting crowds to local wilderness areas include good weather, the opening of new trails and facilities in the Santa Monica Mountains, the popularity of online “meetups” for hikers and even a trend toward stay-at-home vacations.

In Malibu, that adds up to what may be the busiest season yet for the local rescue team, made up of about 30 reserve sheriff’s deputies and civilian volunteer specialists and support staff.

Coming off last year’s record-setting 128 call-outs, the team as of last week had logged 75 responses in 2012, compared to 68 at this time last year. “And we haven’t gotten into August yet,” said Jeremy Littman, a television writer who keeps the stats for the team and serves as its lieutenant.

Two people have died, one of them a suicide, at Rindge Dam in the past eight or nine months, said David Katz, another member of the team who also acts as its public information officer. Others have been injured jumping off the dam into the water below—a stunt immortalized in YouTube videos, some of them set to music.

“It’s a dam. It’s not built for playtime,” Katz said. “It’s a dangerous area and if you do get injured and have to be evacuated, you’re 600 feet deep in a canyon.”

The surge in rescue calls isn’t limited to Malibu. Through June, calls were up year-over-year for all but one of the county’s eight search and rescue teams.

“It sure has been an active few months across the county,” said Michael Leum, assistant director of the sheriff’s Reserve Forces Bureau and reserve chief of its search and rescue operations countywide. “It’s been super-busy, with people staying around locally and doing the ‘staycation’ thing. On Sunday alone, Crescenta Valley had 10 different response calls.”

And Friday, July 13, proved to be a particularly unlucky day for hikers in Eaton Canyon—and an exceptionally demanding one for rescuers, who had to make three helicopter rescues within the space of an hour.

In Leum’s view, one of the risk factors for getting in trouble on the trail is simply being male.

“Ninety-nine percent of the people we go looking for are guys who go out by themselves and don’t tell anyone where they’re going,” Leum said.

Added Sgt. Tui Wright of the Malibu/Lost Hills Sheriff’s Station, who oversees the area’s search and rescue team: “There really is a lack of common sense out there and people do a lot of things to put themselves in peril.”

Still, you don’t have to be a thrill-seeker to run into trouble, said Malibu search and rescue team captain Mark Campbell. “Some things do happen to well-meaning people,” he said. Those who want to stay out of harm’s way should file a hiking plan with the sheriff’s department before setting out. (Download one here.) Other tips: allow plenty of time to complete the hike before dark; carry water, food and warm clothes; pay attention to the weather forecast; and bring along a well-charged cell phone.

Carrying a phone is particularly important. Because while technology leads some people into trouble, it also can help lead them out of it—sometimes in unexpected ways.

Consider the case of the 17-year-old hiker, stranded last month on a steep ridgeline, who used the light from his iPhone to help rescuers find him and whisk him to safety.

Posted 7/25/12

The Malibu search and rescue team is looking for volunteers. Details on how to join are here.

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink