Next stop? A milestone in public art

April 11, 2013

Donald Lipski's "Time Piece," part of Metro's signature art collection, greets bus travelers at the El Monte station.

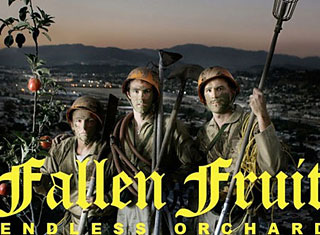

As art collections go, it’s impressive, from famed sculptor Jonathan Borofsky to activist/artist Judy Baca to renowned Eastside painter Frank Romero.

The catch? You have to be traveling to see it. Oh, and a lot of it is literally underground.

The sprawling exhibition of public art that Metro has built in L.A. County’s subway, bus and commuter rail stations will celebrate its 25th anniversary next year. (Take a virtual tour in our gallery below.)

Launched in 1989 with a half-percent set-aside from rail construction costs, Metro’s award-winning collection of public transit art now encompasses work by some 120 artists in 100 stations, plus posters, photography, poetry and other temporary installations by another 180 artists. Last week, eight California artists were selected to create work for the second phase of the Expo Line, which will run to Santa Monica from the end of the first segment at Culver City.

“Art brings a unique vibrancy and vitality to L.A.’s Metro system,” says Maya Emsden, deputy executive officer for creative services at Metro, who is one of a handful of co-authors on a forthcoming American Public Transportation Association “best practices” paper on integrating art into public transit.

“Art was an integral part of the Metro rail planning process from the very start.”

Metro’s collection kicked off in 1990 with a now-highly-collectible poster by Romero to commemorate the opening of the first Metro rail line. That inaugural artwork, which depicts an old Red Car morphing into the Blue Line as classic cars, blimps and airplanes whiz around it, was followed the next year by “Unity,” a glowing, blue-and-white permanent installation of 82 fiber-optic light panels in the subway tunnel between the Metro Center and Pico Stations by Thomas Eatherton, an artist from Santa Monica.

That piece led in 1993 to a series of now-iconic permanent artworks: Borofsky’s “I Dreamed I Could Fly,” a collection of life-size fiberglass figures suspended from the ceiling of the Civic Center station; Terry Schoonhoven’s Union Station mural of “time-scapes” from Spanish galleons to Carole Lombard, sitting on a suitcase; Joyce Kozloff’s ceramic tile “film strip” murals in the 7th Street/Metro Center station; Stephen Antonakos’ hanging neon artworks at the station below Pershing Square.

Since then, the program has expanded with L.A.’s transit system, says Emsden; the new commissions for Phase 2 of the new Expo Line were selected from some 400 submittals and include such artists as Shizu Saldamando, Abel Alejandre, Susan Logoreci, Nzuji de Magalhaes, Constance Mallinson, Carmen Argote, Judithe Hernandez and Walter Hood.

Though the half-percent of construction costs that L.A. reserves is substantially smaller than transit art set-asides in Boston, New York, Portland, and most other cities with such programs, Metro has been able to stretch its allotment by integrating the artworks as much as possible into the station construction.

“One of the ways we’re able to maximize the limited budget is through early involvement in the project,” says Emsden. “This also ensures important art-related things like lighting are integrated into the station plans.”

The added efficiency of building art into a station, as opposed to going back later and retrofitting, is just one of a number of art lessons Metro has learned in the past 24-plus years. Art program staffers have learned to work closely with architects, engineers and maintenance staff to situate pieces so that maintenance of the art is taken into consideration—a matter that can be trickier in, say, a rail station than in a museum.

“The Borofsky piece, ‘I Dreamed I Could Fly’, is one of my absolute favorites,” says Emsden. “But if we were to do it again we’d make sure the figures, which are actually self-portraits of the artist, were hung in a way that we could lower them for cleaning.” The flying fiberglass figures—like everything else in the stations—get covered over time with magnetic steel transit dust that can only be removed with specialized equipment and cleansers, says Emsden.

“So every five years or so, we get up there and clean them between 2 a.m. and 4 a.m.”

Another lesson: Some kinds of art fare better in transit settings than others.

Eatherton’s 1991 light piece, for instance, has been out of order for about six years, due to the technical challenges of maintaining aging electrical elements in a hard-to-reach space. Part of a Jacqueline Dreager sculpture at the Blue Line’s Wardlow station had to be taken out because it was too close to a landscaping sprinkler and was slowly being decomposed by the water. A set of Gilbert Lujan benches at the Hollywood/Vine station had to be refurbished and then eventually removed altogether because vandals kept tagging and carving their initials into the sculpted bench backs.

However, the vast majority of the Metro projects have fared well, says Emsden, adding that even delicate images have been made transit-worthy by rendering them in materials that are sturdy enough for public artwork.

“We’ve commissioned a couple of artists whose whole body of work is on paper, but there are some amazing artisans in L.A. and elsewhere who can translate those artist’s visions into very durable materials,” says Emsden.

For example, one Canadian studio that specializes in mosaics has made detailed lino-cut prints by Sonia Romero and Daniel Gonzalez, paintings by Samuel Rodriguez and photos by Pitzer College associate art professor Jessica Polzin McCoy into intricate Metro panels made of ceramic tile.

Meanwhile, she says, the program has yielded some pleasant surprises. One was the groundswell of interest among local culture enthusiasts asking to do guided art tours. The result, in 1999, was a Docent Council whose volunteers have introduced more than 30,000 people to the art of the Metro system. Notes Emsden: “We’re the only transit agency with volunteer docents and free Metro art tours.”

Perhaps the nicest surprise, however, has been the way in which some Metro pieces have worked their way, just by word of mouth, into the public imagination. “There’s a light piece by the artist Bill Bell that, if you say a secret word into a tiny hole in the wall at the top of the escalators that go down to the Red and Purple Lines at Union Station, the piece will speak back to you,” Emsden says.

There’s no sign. There are no instructions. The artist, by design, held back the “secret word” (the names of any of the various celebrities depicted, from Rin Tin Tin to Dizzy Gillespie) and left no clue that any extra magic might be found there. “But I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen someone going past there—a security guard, a commuter, a business person—and saying to the person next to them: ‘You gotta check this out!’ ”

Jonathan Borofsky’s “I Dreamed I Could Fly” is an iconic—though hard to clean—part of the Civic Center Station.

Public art and public transit come together in the following gallery. All images courtesy Metro.

Posted 4/11/13

Vote and help spread a cool $1 million

April 11, 2013

The candidates are out there, stumping for votes, inundating inboxes, taking to Twitter and Facebook to spread their messages.

No, we’re not talking about a certain upcoming mayoral election—although, like that contest, the outcome of this one could have ramifications for the future of Los Angeles.

This hotly-contested race is called MyLA2050, and the candidates, all 279 of them, are vying for a piece of a $1 million pot that aims to underwrite 10 of the best ideas for changing life here for the better.

It’s crowdsourcing with a conscience. And to scroll through the entries is to peer into the idealistic, entrepreneurial, only-in-L.A. psyche of a metropolis in transition.

Want to support a door-to-door urban composting program?

Underwrite a rolling neighborly Potluck Truck?

Jumpstart an off-the-grid, self-sustainable artists’ habitat called ValhalLA?

Here’s your chance to cast a vote—and just one, according to the rules—for the project that captures your imagination, or your heart. While public voting won’t directly award any money, it will determine the top 10 vote-getters in the eight categories from which winners will be chosen by the Goldhirsh Foundation, which is sponsoring the initiative. (The categories are education, environmental quality, health, social connectedness, art and cultural vitality, income and employment, housing and public safety.) Two other “wild card” projects will be selected as well—regardless of whether they receive popular acclaim. Each of the 10 winners will receive $100,000 to implement their idea.

On social media, the politicking is getting fast and furious as the voting deadline—high noon on April 17—approaches.

“HoneyLovers! Can you spare 30 seconds to help us out? We are in the running for a $100,000 GRANT to help make Los Angeles PESTICIDE FREE! We would LOVELOVELOVE your support! PS—You do not need to live in Los Angeles to vote for us so spread the buzzzzz!!!” read one appeal on Facebook from the beekeeping-promoting HoneyLove (aiming for a “Pesticide-Free Los Angeles 2050.”)

And that’s far from the only get-out-the-vote effort going. “We are gaining momentum in the voting. We are not there yet,” said a recent post on behalf of the Potluck Truck candidate from Project Food Los Angeles. “One of our members is counting on this grant to tell her father to back off the consistent pressure to get a real job! A victory here would be a strong validation of the power of ideas…we think it’s a good one! Please VOTE!”

Some, like the Eagle Rock Yacht club, which promotes dodgeball as a gateway to youth education programs, are offering incentives: folks who vote for the project get $10 off the $45 fee for the organization’s spring leagues.

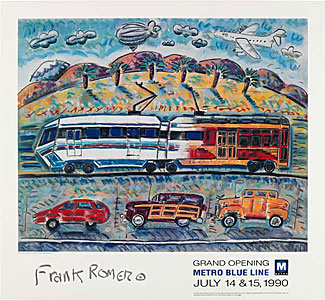

Fallen Fruit's "Endless Orchard" envisions fruit trees and mirrors combining to make an art project full of contrasts.

In the midst of the all the competing appeals, however, some would-be voters seem stymied by the contest rules, like one who recently asked on Facebook: “Am I the only one who finds this confusing? Can we vote for one each in multiple categories? Or just for one? I have so many friends who are competing for this!”

Others have run into frustration because the voting website won’t open on older versions of Internet Explorer. (Contest organizers suggest using Firefox or Chrome browsers.)

“At first it was kind of nail-biting because I’m very passionate about the idea and I wanted everybody to hear about it. I was blasting it out there,” said Courtney Carter, who’s promoting the ValhalLA artists’ habitat. She said she’s been checking the contest leader board “like every second” to see how her entry is faring with the voting public.

Vivian Liao of City Earthworm, who’s behind “You Can Compost That!” has also been an energetic stumper.

“I do a lot of Facebook and Twitter campaigning. Obviously, there’s a lot of friends-and-family bugging,” she said. “I’m blogging about this also.”

It’s understandable that some people are having a hard time choosing which program to back. There are entries from famous institutions like the county Natural History Museum (proposing an Urban Safari program to “discover and document” the biodiversity of the L.A. Basin) and candidates from tiny outfits like HoneyLove. Naomi Ackerman’s Advot Project seeks to change the lives and relationships of teenagers through theater and dramatic exercises. Community Builders Resource Network wants to bring charitable organizations together for greater impact.

Some contenders grew out of established success stories, like the heartwarming international video sensation Caine’s Arcade, or L.A.’s favorite car-free rolling block party, CicLAvia. Others are more niche (“Beautiful Rain Barrels in Public Places.”) Some are big (“The Million Reusable Bag Giveaway”), some are small (“Park-in-a-box”), some sound like poems (“Endless Orchard”) and some sound like they’re on a mission (“Empowering Teens with the Knowledge and Skills to Make Healthy Decisions.”)

There are concepts for apps and maps and pop-ups. Garden-related ideas are huge, and there are a number of proposals advancing new, socially-conscious purposes for food trucks. The Los Angeles River figures in at least two: A temporary summer riverfront park and an Elysian Park “swimming pool/industrial cistern” to be used as a public plunge.

And like any campaign, there are the catchy slogans and exhortations: “Kids who sling kale eat kale,” ”Dodgeball, prosperity and the Common Good,” “State of the art lighting for city parks!”

The contest is part of a broader initiative, sponsored by philanthropist and GOOD magazine founder Ben Goldhirsh, to rethink the future of L.A. A report—“Los Angeles 2050: Who we are. How we live. Where we’re going.”—was released in February, with the aim of stimulating “an outbreak of idealism that strengthens civic engagement, challenges the status quo, and demands more for the future of Los Angeles.”

Shauna Nep, a social innovation manager on the project, said the contest is a way to bring more attention to the findings in the report and to “create a more participatory and transparent process” for tackling some of the challenges it explored.

The $1 million derby brought out a wide range of entrants, she said—“a lot we were familiar with, and some we’d never heard of before.”

And, while it has not received much attention in the mainstream media, she noted that it has been a lively topic on blogs and social media networks.

“We’re overwhelmed,” she said.

Meanwhile, don’t worry that you’ll have to wait around till 2050 to see your favorite innovations take shape. The rules call for all the winning projects to be implemented this year.

Posted 4/11/13

For Hollywood, no splendor in the park

April 5, 2013

The scene at Grand Park, where film executives have complained about high fees. Photo/Shabdro via Flickr

Lucas Rivera had barely gotten his feet wet in Grand Park’s beautifully restored fountain when Hollywood came calling. Sony’s Screen Gems told the park’s newly named director that it wanted to use the Arthur J. Will Memorial Fountain in a scene for an upcoming remake of the romantic comedy “About Last Night.”

But what studio executives say they heard from Rivera last fall was no laughing matter. The price to film in L.A’s hippest new green space was $20,000 for each of the park’s four blocks—the steepest fee for any publicly-owned venue in Los Angeles.

Lucas, who was swamped with planning the park’s gala grand opening at the time, says the request “came at us out of nowhere.” The filmmakers repeatedly insisted on lower rates but Lucas says there was nothing he could do because the fees had been formally set by the county. Already committed to the location, the studio grudgingly paid the $20,000. But that was only the first act of a civic drama that, for months, has pitted county officials against their hometown industry.

Since October, the cost of filming in Grand Park has become a cause célèbre among location scouts, labor leaders and studio representatives, who’ve publicly challenged the county’s commitment to keeping entertainment jobs in the Los Angeles region. Screen Gems is the only studio so far to pay Grand Park’s high price of admission. In interviews and in testimony before the Board of Supervisors, industry officials have argued that the high film fees at Grand Park and such famous county-owned venues as the Hollywood Bowl, Walt Disney Concert Hall and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art are contributing to the long-running exodus of Hollywood jobs to more film-friendly locales in the U.S. and abroad.

“These are iconic Los Angeles County landmarks and we are turned away from filming them due to high fees or rules that seem designed to discourage production companies to even consider approaching them rather than embracing this cornerstone industry that helped create part of the rich history that is Los Angeles,” Teamsters official Ed Duffy, who represents location managers, complained to a receptive Board of Supervisors last October. The board ordered a review of the controversial rates by the Chief Executive Office.

On Tuesday, the board is expected to vote on a new permit structure for Grand Park proposed by the county CEO in the wake of the industry’s complaints. The proposed rates have been slashed by 74%, but the fees are still prohibitively high for a public park, industry representatives insist. The county says its goal is to strike a balance between the economic needs of the entertainment business and the park’s primary purpose as a place “first and foremost for the community to enjoy.”

Rivera understands Screen Gem’s case of sticker shock and acknowledges that the initial rates didn’t achieve the right balance, which he mostly attributes to the park’s growing pains.

“We’re young, we’re going to make some bad choices,” Rivera says. “But this is a learning process. With all the people involved, we’re going to get it right…My main concern has been to program the park and make it a destination place for Angelenos.”

So far, he seems to be succeeding.

The park, with its unique cityscape surroundings and dramatic view of City Hall, has been widely praised for its programs, from noontime yoga sessions to a weekly farmer’s market to a presidential election-night viewing party broadcast live by CNN. The CEO says the park, which is managed by the Music Center, attracted more than 19,000 visitors during its first six months of operation and has established 53 programming partnerships.

Entertainment industry representatives say they fully respect that the county’s No. 1 priority is to make the park a hit with the public.

Philip Sokoloski of Film LA, a nonprofit organization that coordinates and processes film permits, says industry executives “realize the park is for public enjoyment first…They don’t want to displace other activities and uses. They just want to make sure they aren’t priced out of the park.”

Some fee critics, though, even question the county’s rationale, noting that even under the new pricing structure, it would cost $12,000 to rent all four blocks of Grand Park between the overnight hours of 9 p.m. and 9 a.m.

County officials say they based the original and revised rates on those charged by other high-end venues here and across the country, including the Huntington Library in San Marino, a private nonprofit institution that charges $11,000 a day, and the Hollywood Bowl, which costs $17,000 to rent. But industry representatives argue that Grand Park’s pricing should be in line with more comparable county venues, including Descanso Gardens and the Los Angeles County Arboretum and Botanic Garden, which charge daily rates of between $1,500 and $6,400 and are often used for film shoots.

Dawn McDivitt, who oversaw Grand Park’s construction for the CEO’s office and continues to play a key role in its operation, says she hopes the new rates will be approved by the board on Tuesday. She knows that some entertainment industry officials still will be unhappy, but she says the county will evaluate the program in six months. Nobody in the county, she says, is ready to say the issue is a wrap.

“We’ll look at the experience we’ve gained from having filming in the park and its impact on the public we want to serve,” McDivitt says. “It’s all an evolving process.”

Posted 3/21/13

Puppets come out to play in L.A.

April 4, 2013

The "Million Puppet March" in Washington had a goal of saving PBS funding. Only fun is on the agenda for L.A. Puppet Fest.

Stretching their wooden arms, the sleeping puppets of Los Angeles are ready to take center stage.

The puppetry community is full of characters—and not just the wooden or fuzzy varieties. From old-school marionettists to modern dramatists who manipulate 10-foot monstrosities in teams of three, they’re as diverse as the city they live in.

Last September, Joe Smoke of the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs approached Maria Bodmann, an expert in the thousand-year-old art of Balinese shadow puppetry. Together, they pulled a few strings and organized a meeting of L.A. puppeteers with the goal of producing a citywide festival. This month, their plans will come to life at the inaugural L.A. Puppet Fest.

Bodmann hopes the festival will expose people to the many varieties of puppetry.

“People think fuzzy things with eyeballs, but that’s just one little bit of puppetry,” Bodmann said. “There are other types that address issues that aren’t really for kids. The stuff I do is connected to religious rituals. I can’t really do it for birthday parties.”

Pre-festival activities have already begun. From Thursday through Saturday, Rogue Theaters presents “Songs of Bilitis,” a mature audiences-only puppet rendition of the French erotic novel by Pierre Louÿs. The official opening takes place Sunday, April 7, at the Skirball Cultural Center and will feature puppet-making, performances and storytelling. After that, there will be performances by the Bob Baker Marionette Theater, a lecture on puppet history and puppet films and classes. The festival wraps up on April 28 with “L.A.’s largest-ever puppet parade” and closing ceremony at the Third Street Promenade in Santa Monica. See the website for a full schedule of events.

Michael Earl, a co-founder of the Puppet School who had a turn playing “Mr. Snuffleupagus” on Sesame Street a few decades back, said professional puppeteers have been through tough times in recent years.

“When Jim Henson was alive, there was a lot of puppetry happening; they had to train more puppeteers because there were not enough,” Earl said. “Then, 3D animation was invented and it slowly started to replace puppetry jobs.”

But Earl and his contemporaries see puppets making a comeback, due partly to the success of live stage productions like The Lion King and popular box office offerings including Where the Wild Things Are and 2011’s The Muppets.

Cue the L.A. Puppet Fest, which is being called L.A.’s first-ever citywide puppet festival—a description reached amid controversy.

“There is inter-puppet genre conflict,” said Michael Bellavia, who is organizing the puppet parade and closing ceremony. “The puppet geeks, they got all up in arms when this was billed as the first puppet festival.”

Accounts vary. Some point out smaller-scale annual events by the Los Angeles Guild of Puppetry. Alan Cook, co-founder of the guild and curator of the International Puppetry Museum in Pasadena, is a revered patriarch of the puppetry community. He recalls a major, national festival held at UCLA back in 1957. Recorded puppet history in Los Angeles dates back at least 100 years, he said. Worldwide, forms of puppetry go back millennia and represent some of the most respected cultural art forms.

The guild’s current president, Christine Papalexis, said contention among puppeteers is common because they’re artists.

Despite their differences on the minutiae, everyone agrees the festival should be as inclusive as possible. They’re united by a love of puppetry that, for many, began with their first toy puppet in early childhood.

That inclusivity extends to the audience, who will be invited to make their own puppets and learn puppetry skills at some of the events. The L.A. Puppet Fest Parade, for example, will have a puppet-making station on site, and organizers say it’s fine if people just want to draw eyes and a mouth on their hands.

Carved rawhide shadow puppets act out a scene involving the heroic Pandawa brothers of the Mahabharata, a Sanskrit epic from ancient India.

Posted 4/4/13

Front and center at Probation

April 4, 2013

Margarita Perez has brought experience and energy to her new high-profile job with Los Angeles County.

Unlike countless showbiz hopefuls waiting on tables or schlepping to auditions, it didn’t take long for Margarita Perez to land a Hollywood gig. Not that she even thought about breaking into the business when she hit town.

After all, her day job is now among the most important in Los Angeles government. Five months ago, after years in Sacramento, Perez was tapped to help remake the county’s Probation Department and guide its response to California’s controversial AB 109 law, which has placed thousands of former state prison inmates under the agency’s supervision.

On Thursday nights at 7, Perez can be seen hosting a news segment on KCOP-TV Channel 13 called “L.A.’s Most Wanted.” The unique collaboration between the station and the Probation Department calls on the public for tips to help track down five former convicts each week—most of them with serious raps sheets—who’ve disappeared into the community.

“I think it’s exciting,” Assistant Chief Probation Officer Perez says of the segments, which began airing last week. “It’s a great opportunity to highlight probation’s good work and engage the public in holding accountable those offenders who are not availing themselves of our oversight.”

And don’t be deceived by her looks. Although diminutive and fashionable, the high-octane Perez means business. She’s a self-described former “gun-toting parole agent” who broke into the criminal justice system as a guard at Avenal State Prison, a men’s institution in Central California. As an officer in the California National Guard, she was awarded a Bronze Star for meritorious achievement after entering Iraq with the front-line troops during Operation Desert Storm in 1991. “I’m as gung-ho as they come,” she says.

Perez says her parents, born and raised in Mexico, “drove into my head that your success revolves around you. There are no crutches. If you’re not successful, then you didn’t take advantage of the opportunities in this country.”

That advice propelled Perez through the California corrections bureaucracy during a career of more than two decades. Last year, she was put in charge of the Adult Parole Operations Division, where she was responsible for 3,500 employees and a budget of about $650 million.

But that job was increasingly looking like a dead end because of AB 109, the so-called “realignment” law enacted to ease overcrowding in the state’s 33 prisons and save money. As supervision of certain newly released inmates shifted to California’s counties, there was less work for state parole officers, who increasingly faced layoffs. Perez says the number of state-supervised offenders plummeted from 128,000 to 50,000, with only more of the same ahead.

So Perez was ready for a new challenge, a desire that made its way to Los Angeles County Probation Chief Jerry Powers, who assumed the top job in October, 2011, with a mandate to not only implement AB 109 but to also shake-up a department rife with personnel and financial problems. For months, he’d been unable to field a top management team with the expertise he believed necessary to tackle the enormous issues confronting the agency.

“To be honest, I was wearing down,” Powers says. “I was trying to cover the entire house with just me.”

But late last year he found his reinforcements in Perez, whom he hired to oversee adult and juvenile field operations, and in Sacramento County’s former probation chief, Don Meyer, whom he put in charge of the department’s juvenile halls and camps, which had a history of problems so severe that the U.S. Justice Department was compelled to intervene.

Powers says his two new assistant chiefs, outwardly, couldn’t be more different.

“She’s like a tiny little dynamo,” he says. “She talks fast, she walks fast, she works fast. Everything about her is fast.” Meyer, on the other hand, is “a beast,” Powers says, a “barrel-chested” weightlifter who’s competed in and won international law enforcement competitions.

“It’s ridiculous when they stand side-by-side,” Powers says with a laugh. But both, he adds, share this in common: “They get things done.”

Of the two, Perez will certainly play a more visible role—even beyond her TV spots—given the rising concerns and controversy over the potential impact of AB 109 on public safety.

In recent months, two high-profile crimes were allegedly committed by suspects sent to the county for supervision after serving prison terms for non-violent, non-serious, non-sexual offenses. Under the new law, prior criminal histories are not considered when determining an inmate’s post-release supervision, except for high-risk sex offenders, sexually violent predators or “mentally disordered” offenders, who remain under state supervision .

In December, one of the county’s new wards was charged with a quadruple murder in Northridge. Then, just last week, another was named as the prime suspect in the kidnapping and sexual assault of a 10-year-old girl. He remains at large.

Critics of realignment have suggested that such crimes might not have been committed had the state not hurriedly foisted AB 109 on the counties—a contention disputed by most law enforcement officials, including Powers. He says that in 2010, the year prior to AB 109’s passage in Sacramento, more than 170 men were arrested in Los Angeles County for murder while under the supervision of state parole officers.

“If you take 11,000 offenders from the state and put them in Los Angeles County, you can predict that a portion of those offenders are going to kill people and you can predict that a portion are going to rehabilitate themselves and never get in trouble again,” Powers says. “So whatever your philosophical perspective, you can make a prediction and be right because the population we’re dealing with is so large. Having said that, the question is: Can we handle this population with better outcomes than the state?”

Perez says the disclosure that the alleged Northridge gunman was an AB 109 offender came during her first weekend on the job. Some of the probation officers, she says, were shocked because they’ve been mostly accustomed to dealing with lower-level offenders. Not her.

“In parole, this was a regular occurrence. You literally become accustomed to it,” she said the other day from the department’s drab and dated Downey headquarters. “Whether you’ve got a parole agent watching you or a county probation officer watching you, you’re going to commit a crime if that’s your intent.”

She says she tells her probation officers that a good number of the offenders they’re now responsible for supervising were once under probation’s watch for less severe crimes. “The only difference,” she tells them, “is that they’re a little older, their rap sheets are longer and they’re more sophisticated. But it’s the same population you dealt with.”

Perez says she also wants to assure the public that her agency “is ready to take on this challenge. We’re familiar with this population in terms of their risks, their needs and what we need to do to assist them in their reintegration into the community, realizing there’s always going to be some who are either not ready or not amenable to the resources and interventions we can provide to them.”

Perez says was one of her biggest challenges is how the agency can quickly build an infrastructure to handle the new supervision demands, ranging from training and hiring scores of new probation officers to modifying computer systems to improve tracking of the county’s new charges and their progress—or the lack of it.

Also at the top of the list is the screening and training of 100 probation officers who’ll be given guns, a first for the department.

“When I was a parole agent, I carried a caseload and I carried a gun,” Perez says. “The job was to make random house calls in the evenings, during the day, on weekends. And to go into some of those communities that are sometimes dangerous, gang infested, they are just not the safest places in the world. So if there’s an expectation that probation officers are going to do this, you have to give them the tools.” So far, she says, 28 probation officers have been cleared to carry firearms.

Perez says one of her other challenges, on a personal level, will be to find time to continue her practice of Bikram, or “hot,” yoga—27 postures practiced in a room with temperatures exceeding 100 degrees. Perez, a youthful 50-year-old, acknowledges that she practically vibrates with energy.

“You should have seen me before I started yoga,” she says. “It helps me refocus and keep my calm. It gives me a chance to go on autopilot and think about nothing.”

Even if it’s only for a couple of hours.

Posted 4/4/13

From museum gardener, seeds of change

April 4, 2013

Florence Nishida's Natural History Museum class has sprouted gardens all over L.A. Photo/Gordon Hendler

For some, spring is a chance to plant a few tomatoes. For Florence Nishida, it’s an opportunity to re-landscape the face of Greater L.A.

This month, for example, the 75-year-old master gardener will be checking in on some of the 20 or so South Los Angeles yards she helped turn into vegetable gardens. She’ll be sizing up a front lawn and a parkway for makeovers by Los Angeles Green Grounds, the urban gardening group she co-founded.

She’ll be monitoring the community garden she recently did in Koreatown for the new First 5 initiative, Little Green Fingers, and following up with the Los Angeles Conservation Corps on the raised beds she devised for outside their East L.A. office. Then there’s the LA Green Grounds table to set up and man for Earth Day at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, not to mention the regular Sunday gardening workshops she conducts at the museum.

And this is the former schoolteacher’s idea of retirement.

“From years and years ago, it has been my goal,” explains Nishida, “to have a vegetable garden and a fruit tree on every block in L.A.”

Nishida isn’t the only urban gardener on a mission these days in Los Angeles County, but lately, she has been among the more productive ones. Since 2010, when she persuaded the Natural History Museum to let her install a small teaching garden on its Exposition Park campus as part of an inner-city community project, her green thumb has been in many, if not most, of the urban gardening projects that have sprouted across the city like backyard zucchini.

One of her first students, artist Ron Finley, has won international acclaim with a pair of TED talks on urban gardening. Her former teaching assistant, the museum’s public programs manager Vanessa Vobis, is among at least five protégés who have gone on to become fellow master gardeners. Green Grounds, which she co-founded with Finley and Vobis, has literally broken new ground in South L.A., where the group has worked one yard at a time, installing gardens at volunteer “dig-ins” to help under-served neighborhoods grow their own organic produce.

Nishida herself has been called in increasingly to consult on community gardening projects throughout the county. Meanwhile, her edible garden at the Natural History Museum has drawn some 150 students just to the beginner’s workshop; this year, her class will expand to the new Erika J. Glazer Family Edible Garden, a showplace of fruit trees and seasonal plantings that will open officially in June with the rest of the museum’s new Nature Gardens.

“The museum was ground zero,” Nishida says now. “It all started from that class.”

Nishida hasn’t always seen gardening as a road to anyone’s revolution. A native Angeleno, she says, home gardens were a fact of life for her Japanese-American relatives throughout Southern California and in the Exposition Park neighborhood where she grew up.

“After World War II, my grandparents resettled in West L.A. near Sawtelle and grew vegetables in their front yard, as did a lot of people,” she remembers. But as time passed and L.A.’s economy shifted, fast food joints, un-walkable streets and dense apartments crowded out the kitchen gardens and mom-and-pop produce stands, gradually eroding the city’s health and turning organic produce into an upper-middle-class status symbol.

As Nishida moved to Topanga, worked and raised her four children, she says, she always held a notion that her old, blighted neighborhood might be restored if someone could bring back the green space. Eventually—after 20 years as an English teacher in the Los Angeles Unified School District, another 20 as a bureau manager and research librarian at People magazine’s West Coast Bureau and a graduate degree in botany that resulted in a sideline as a mushroom expert at the Natural History Museum—she decided to revisit her old theory.

“I had seen a little article in the Los Angeles Times about the master gardening program at the UC Cooperative Extension,” she remembers. “It was a tiny little article, but for whatever reason, I just saved it.” When she retired in 2008, she says, she took the classes, which require, among other things, that graduates go on to lead community gardening projects in under-served parts of their cities; one of her early projects was a home garden that later served as a model for Green Grounds. Another was a plan to bring gardening knowledge to Exposition Park by launching a class at the museum.

That idea—which dovetailed with the museum’s centennial plans to re-landscape its North Campus into a “living laboratory”—led to her meeting with Finley, an experienced gardener in his own right who had signed up for her class after he had noticed another master gardener’s project near Dorsey High School. Soon Nishida was asking Finley for advice on how to bring more neighborhood people into her museum classes.

“I told her, ‘They’re not gonna come to your classes—they got Burger King, they got Kentucky Fried Chicken’,” recalls Finley. “We gotta take it to them.” That, he says, was the start of Green Grounds, which effectively installs free gardens in people’s front yards in the style of an old-fashioned barn raising, and which has taken off since Finley’s second TED talk in February.

“We got people driving in from Ventura,” he marvels. “I’m like, damn! Is it that boring in Ventura? I mean, we had over 300 people sign up at our last dig-in, and all we needed was 15.”

Nishida says Green Grounds has been an education, not only in the art of managing volunteerism but on the laws of nature in L.A. Their first garden flourished for three months, only to be destroyed by the homeowner’s German shepherd. Another garden fed a family for nearly half a year before they were evicted. A third fell prey to a local gang she’d never heard of—gophers. Finley famously fought with the City of L.A. over the parkway he wanted to replant outside his house.

Nonetheless, Nishida says, 13 of the Green Grounds gardens are still blooming, with more in the pipeline; recently the group set up a fiscal sponsorship with the L.A. Community Garden Council to handle the influx of donations since Finley’s TED talks. And those gardens have, in turn, been change agents: Neighbors have gotten to know each other over samples of fresh produce, she says, and exercise groups have sprung up among dig-in volunteers and recipients of gardens.

In fact, she says, her only disappointments have been that the movement hasn’t spread faster, and that her commitments have left her so little time to tend to her own yard.

“Oh, it’s awful,” she confesses, laughing. “My vegetable beds are overrun with weeds.”

Posted 4/4/13

Trying to beat Dodger traffic blues

April 4, 2013

Every spring, it happens like clockwork: Vin Scully’s voice lilts across the metropolis, Dodger dogs become an essential food group and downtown L.A. resigns itself to 80-plus nights of traffic headaches.

This year, though, there’s an upstart rookie in town: a 1.5-mile dedicated Dodger Stadium Express bus lane running along Sunset Boulevard, aiming to revolutionize how the getting-to-the-stadium game is played.

With the Dodgers under new management and the stadium freshly spiffed up with a $100 million renovation, aggressive efforts are underway to crack one of L.A.’s thorniest traffic dilemmas—getting fans into and out of Chavez Ravine when most home games overlap with downtown’s always lively afternoon rush hour.

“There’s no room for error,” said Aram Sahakian of the city Department of Transportation’s special traffic operations division. For the home opener Monday, “we threw everything we had at it.”

It paid off on the first day, he said: “I don’t think ever in Dodgers history we’ve cleared [stadium traffic from] Sunset on Opening Day before the first pitch…It was a huge success.”

But while ridership on the Dodger Stadium Express buses is up—9,750 so far this year, compared to 7,157 at the same time last year—general traffic downtown this week has been, well, foul.

“Obviously, when you take a lane away, it will have an impact,” Sahakian said, “but it’s also driver behavior. There’s some tweaking to be done.”

The new lane on Sunset, while a boon to game-goers who ride the express buses, is clearly confounding some drivers.

“It’s new to motorists; they don’t know what it is,” Sahakian said of the dedicated lane, which begins at Figueroa and runs through Elysian Park to the stadium.

Those used to driving in the curbside space now taken up by the new, 12-foot-wide bus lane will need to adjust by changing their lane choice, or their route, he said. And those headed to the game by car should give some serious thought to taking the bus next time. (The buses depart from Union Station at 10-minute intervals before each game, and every 30 minutes while the game is in progress.)

Other adjustments also are in the works. Sahakian is proposing that the city’s Automated Traffic Surveillance and Control system be up and running for all home games, as it was on Opening Day, so real-time adjustments can be made to traffic signals. Sahakian also is suggesting that cars carrying four or more people be allowed to use the special lane.

“We’re brainstorming,” he said. “It’s a challenge. The venue, the location, is a challenge for us.”

This year, enthusiasm about the team and its new owners means likely higher attendance, with 20 games already sold out, Sahakian said. And that means heavier traffic.

“We know attendance is going to be very high. We’re excited about it, but with that comes challenges.”

Renata Simril, the Dodgers’ senior vice president for external affairs, said the organization is heavily promoting Dodger Express bus ridership and the new dedicated lane, including on Scully’s popular broadcasts.

She said the Dodgers have also made adjustments to make it quicker for motorists to get into the stadium parking lots. “Ambassadors” now walk down lines of waiting cars to accept parking payment. (They’re still accepting cash only, but by next season should be equipped with mobile devices that will allow them to take credit cards.)

In addition, the ballpark is opening half an hour earlier before games—at 4:30 p.m. for a 7:10 p.m. start.

“Every little bit helps,” Simril said. “We’re trying to take a multi-pronged approach.”

The Dodger Express buses, which are free to riders with a game ticket and $1.50 each way for other passengers, run on clean-burning compressed natural gas and are funded by a two-year, $1.1 million grant from a regional air pollution reduction committee.

City officials and the Dodgers are hoping that increasing express bus ridership will reduce the number of cars coming into the stadium, and the dedicated lane on Sunset is seen as an important tool in persuading people to hop aboard.

“Taking one lane away is going to impact people driving to the stadium,” Sahakian acknowledged, “but at the same time, you’re incentivizing mass transit.”

Looking at the long-term picture, though, Sahakian thinks a bolder solution may be called for.

“My personal recommendation,” he said, “would be a monorail.”

Posted 4/4/13

The Ford says take a seat. Or two.

April 3, 2013

Maybe you’ve settled into one on a clear autumn evening and basked in the cool stylings of the Angel City Jazz Festival. Perhaps you took a load off to catch Jane’s Addiction in 1989—or their sold-out return in 2011. Possibly you leaned back as Elvis Costello performed songs from a new album in 1996, or sat up straight in amazement at the tap-dancing virtuosity of Fayard Nicholas in 2000.

L.A. audiences have been parking their posteriors in the sturdy brown seats of the Ford Amphitheatre for more than three decades—ever since its original wooden pew-style seating was ripped out in 1980.

Whether you’re an aficionado of Mexican folk ballet, Outfest movies, exuberant Brazilian Nites or the family-friendly antics of Big!World!Fun!, chances are you’ve made yourself at home in one of the historic amphitheatre’s 1,200 seats.

Now one of those seats can make itself at home with you.

The chance to own a piece of Ford history comes as the old seats were removed this winter to make way for waterproofing the amphitheatre’s floor, and new seats, in shades of soft gray and green, are being installed this spring. The work is part of a larger overhaul, to be completed by the summer of 2014, in which the stage will be redesigned, lighting and sound systems replaced and the scenic hillside behind the stage re-landscaped. Architect Brenda Levin, whose firm masterminded recent improvements at Dodger Stadium and in 2006 completed the historic renovation of Griffith Observatory, is heading up the project, with Mia Lehrer overseeing the landscaping.

This off-season’s work is all about making the outdoor facility much more water-tight.

“We were leaking like a sieve,” said Laura Zucker, executive director of the county Arts Commission, which manages the Ford. She said leaks through the amphitheatre floor have seeped into everything underneath, including the facility’s restrooms, bar area, storage room and small indoor theatre.

The old seats are still in good shape but were major culprits in the leaking because each required 8 bolts to secure.

The Ford Theatre Foundation, the non-profit organization that supports the amphitheatre and its programming, is selling the retired seats for $50 each ($90 for a pair, and greater discounts for larger purchases up to four.) The form to order the seats is here; information on when and where to pick up the seats will be noted at the bottom of your emailed receipt. Please note: the seats are not freestanding, and must be secured with bolts.

Any seats not sold during the fundraising drive will be donated to local parks or other outdoor venues that could use them, Zucker said.

The Ford, originally called “The Pilgrimage Theatre” in a nod to the religious play that in the early days was regularly performed there, opened in 1920 and was rebuilt after it was destroyed in a 1929 brushfire. It has been owned by Los Angeles County since 1941 and was renamed to honor former Supervisor John Anson Ford in 1976. Its “Partnership Program,” focusing on showcasing and developing local performing arts groups, started 20 years ago and is still going strong.

“The Ford is the only performing arts venue in Los Angeles that exists to support and present Los Angeles-based artists,” Zucker said, quipping that the “locally-sourced” programming comes with a guarantee that “all performers are grown within 100 miles of the venue.”

Tickets for this summer’s season go on sale April 10. [Updated: The Ford's summer schedule is here.]

Posted 4/3/13

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information