Top Story: Environment

Seeing stars in rural Los Angeles

November 14, 2012

Welcome to the dark side, Los Angeles County. This week, the Board of Supervisors officially cracked down on light pollution in the county’s rural areas.

Long awaited by unincorporated communities in the Antelope and Santa Clarita valleys and the Santa Monica Mountains, the county’s new “Dark Skies” regulations—approved earlier this year, but delayed to hammer out some technical language—mark the county’s first comprehensive effort to restrict outdoor lighting in sparsely populated parts of the county where the sight of the Milky Way at night is as cherished as ocean views are to beach dwellers.

“One of the primary complaints we get from residents is urbanites coming out into their rural communities and brightening their acreage,” says Bruce Durbin, supervising regional planner for ordinance studies with the county Department of Regional Planning. “People understand that there are natural resources to protect, and even in an urbanized county like Los Angeles, there are still rural areas where people want to live that rural lifestyle, and the night sky is a defining element of that.”

The new regulations, which take effect December 13, create a Rural Outdoor Lighting District that encompasses not only the Santa Monica Mountains and the rural areas in the northern part of the county, but also much of Catalina Island and rural unincorporated areas in the East San Gabriel Valley around Rowland Heights and Diamond Bar. (For a map, click here.)

Within that area, outdoor lights will have to be shielded so the light faces downward and doesn’t “trespass” on neighboring properties, and output will be mostly limited to 400 lumens, or about as bright as a 40-watt incandescent bulb. Most commercial and industrial lights will have to be turned off between 10 p.m. and sunrise, and recreational facilities will be encouraged to use high-pressure sodium or metal halide lamps to keep glare down.

Jails, prisons, probation camps and other such secure facilities will be exempted, as will sites such as marinas, aviation facilities, theme parks and petroleum processing plants, which require security lighting. However, most properties—including the county’s—will be covered, although existing street lights will be dimmed only as they’re replaced.

The goal, Durbin says, is to keep the glare from eclipsing the night sky and confusing the nocturnal wildlife that rely on the dark to find their way. The regulations will also bring uniformity to unincorporated communities, many of which had localized outdoor lighting standards that were vaguely worded or unenforceable.

Property owners will have until June, 2013, to come into compliance, says Durbin, although those who want to get a jump on the new rules can click here for this useful interim guide. Official brochures will be available in January at county field offices, libraries and public information counters at the Department of Public Works and Department of Regional Planning, he adds.

Light “trespassers” will have six months from the date of notification to dim their lights. If a light is too bright for the law, but the glare doesn’t “trespass” onto someone else’s property, the grace period could last for as long as three years, he says.

The regulations will be enforced by county planning and zoning inspectors, who will use photometers to measure light trespass complaints. To file a complaint, residents can contact the Department of Regional Planning Zoning Enforcement at (213) 974-6453 after December 12, or dial the County Helpline 211.

Rural Angelenos applauded the measure.

“If the ordinance works as intended, we’ll keep our night skies and views of the stars, owls and other nocturnal hunters will still be able to find their dinner and some of our neighbors can finally get rid of their bedroom blackout curtains,” says Mary Ellen Strote, a longtime resident of the Santa Monica Mountains.

“A lot of us have been waiting for this ordinance since the 1970s, when people started bringing ‘city’ lighting into the mountains. It’s a real gift to the county’s rural residents.”

Posted 11/14/12

Big wheel turning

August 8, 2012

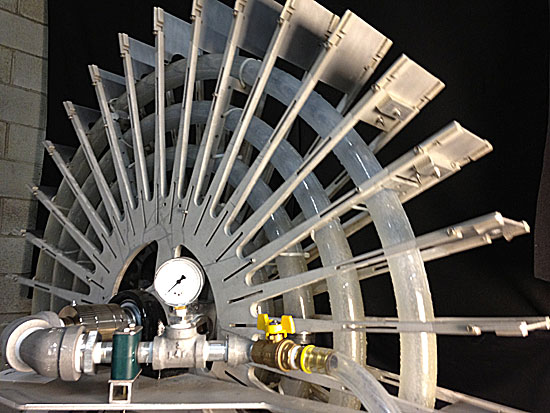

The water wheel, shown above in early prototype, would reconnect L.A. to its river and irrigate the state park.

Lauren Bon planted green rows of corn on a once-forsaken brown field in downtown Los Angeles. She enlisted military veterans to help her cultivate strawberries hydroponically on the V.A. grounds in West L.A. And now she’s preparing to make another big statement—in the form of a massive, working water wheel intended to reconnect Los Angeles with its river, its history and its current environmental realities.

The water wheel is the central element in an ambitious artwork/environmental project to be created next year on a sliver of land beside the Broadway bridge over the L.A. River. The site is right next to the Los Angeles State Historic Park at the edge of Chinatown, where Bon’s “Not a Cornfield” transformed the landscape in 2005.

Drawing on the historic water wheels that dotted Los Angeles from 1854 to 1900, this latest endeavor is being timed to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the dedication of the Los Angeles Aqueduct—November 5, 2013. The project seems destined to spur new discussion of the landmark moment in Los Angeles history when William Mulholland first watched Owens Valley water transported along the 233-mile aqueduct gush into the San Fernando Valley and famously declared, “There it is. Take it.”

While the aqueduct’s legacy has been seen variously—and often simultaneously—as an environmental tragedy, a monumental rip-off and an essential step in enabling the growth that created modern day Los Angeles, the water wheel project seeks less to judge than to inspire fresh thinking about the future.

“I think it’s really critical for us to take a pause and think about our definition of the city,” Bon says. “My position is that it’s time to look at the next hundred years. This work is about saying we need to do a lot better very quickly with figuring out two things: how to retain our water and how to send the rest of it out to sea cleaner.”

Indeed, the water wheel—to be known by its Spanish name, “LA Noria”—is expected to play a hard-working role that goes well beyond its aesthetics. Powered by the flow of the L.A. River, the turning wheel would lift river water in buckets high above the ground. The lifted water would be filtered, transported via a flume or pipe and used to irrigate the 32-acre state park while the rest rejoins the river on its way to the ocean. The project team estimates the wheel could provide 28 million gallons a year for park irrigation, potentially a $100,000-plus annual savings.

Mark Hanna, an engineer with Geosyntec Consultants who is working on the project, says the river, with 80 cubic feet of water per second flowing through “at the lowest point in the driest season,” is perfectly capable of powering the wheel.

The project to build the 60-foot wheel, with 30 feet visible above ground, is being developed and designed by Bon and her Metabolic Studio, a philanthropic endeavor of the Annenberg Foundation, of which she is a vice president and director. Exact costs aren’t yet known but are expected to reach several million dollars by the time the project is finished.

Building the wheel is one challenge. Navigating the complex maze of official permissions needed to make it a reality is another.

The public affairs lobbying firm Kindel Gagan has been hired to obtain the approvals and permits, and the firm’s Michael Gagan says he’s encouraged by initial meetings with the vast array of agencies involved.

They include the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which owns the land, and the county Department of Public Health, which must issue a permit allowing use of the river water for irrigation. No fewer than four city departments also must sign off on different aspects of the plan—Water and Power, Planning, Building and Safety and the Bureau of Engineering—along with the state parks department, the Regional Water Quality Control Board, the county Flood Control District and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Metrolink, whose trains run right past the site regularly, also is an interested party.

The Los Angeles River Cooperation Committee, a joint city-county working group that evaluates upcoming river projects, gave the water wheel its blessing at its July 9 meeting. “We think it’s super-exciting,” said Carol Armstrong, who heads the L.A. River Project Office of the city Bureau of Engineering.

At the moment, the clock is ticking—literally—inside the studio, where an electronic red countdown sign marks off the time remaining until the aqueduct’s 100th anniversary.

Still, Bon doesn’t doubt for a minute that her project will be able to beat the clock.

“It’s gonna happen,” she says.

A community activist shared this model depicting the neighborhood's original water wheel as it might have looked in the 1850s.

Bon, who always likes to introduce what she calls a “device of wonder” into her projects, including “Strawberry Flag” at the V.A. and “Not a Cornfield” in the State Historic Park, sees the water wheel as a natural extension of that work. “These aren’t just surprising little projects that are popping up,” she says. The water wheel is “part of three signature projects that all share a definition of the city.”

The wheel also relates to another project currently underway called “Silver and Water.” That expansive, multimedia work-in-progress aims to tell the story about how the “alchemy of photography and Hollywood,” fueled by silver mined in the Inyo ranges and water from the Eastern Sierra, helped create the movies—and Los Angeles itself. One of the project’s elements is a traveling “liminal camera”—basically a massive pinhole camera capable of taking huge photographs—that has been built in a reclaimed container on a flatbed truck.

On a recent day, the liminal camera, which Bon dubs “the largest pocket instamatic camera in the world,” was parked outside the studio, close to where the water wheel would be built.

Inside, another machine, in the form of a working, aluminum prototype of the proposed water wheel, stands ready to make a public debut this week. While the model doesn’t show exactly how the water wheel will function in its final incarnation, it will be Exhibit A at a community open house on Thursday, August 9. The gathering runs from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. at Metabolic Studio, 1745 N. Spring St., Los Angeles, with the parking and entrance located off Baker Street.

Even before the open house, Solano Canyon resident Alicia Brown said awareness of the water wheel project is building in the area. “Most of my neighbors, they know. Some have taken it lightly; others are amazed,” says Brown, who’s lived in the neighborhood since 1939.

Brown dropped by Bon’s studio recently with her own tabletop model of the historic water wheel that in the 1850s served her community, not far from where Bon’s project is to be installed. An architecture student built the model and gave it to her years ago; now she thinks it could help inspire the new incarnation. Although it’s likely that the new water wheel will be made of metal, Brown is holding out hope for wood, to more closely replicate the original.

“I’ve always loved this neighborhood so much,” says Brown, a neighborhood activist and history buff who for years has been fascinated by Solano Canyon’s vanished water wheel. “There was one there, and people should know.”

Artist Lauren Bon with Metabolic Studio's "liminal camera," near the site of the proposed water wheel installation.

Posted 8/8/12

Do beach report cards make the grade?

June 14, 2012

Summer is almost here, with news from the coastline: More than 80% of the county’s beaches are clean.

Or are they?

Beach report cards such as those generated by Heal the Bay and Los Angeles County raise public consciousness and spur crucial cleanup efforts. But what do they really mean?

Chad Nelsen, environmental director of the San Clemente-based Surfrider Foundation, says he views beach grades and report cards as a rough-but-useful guide to a beach’s overall cleanliness and history. Beach grades aren’t same-day evaluations, he notes, and they don’t yet say enough about why a beach’s bacteria level may be elevated.

“Any given beach can be clean on any given day, but these kinds of report cards look at the average,” says Nelsen. “They can tell you if a beach is chronically polluted or typically clean.”

Beach grades are culled from ocean water samples collected from hundreds of coastal locations. In Los Angeles County, the Department of Public Health samples the water weekly at 40 sites between the Ventura County line and the Redondo Beach Pier, plus five sites between April and October at Avalon Beach on Catalina Island.

In addition, the department reviews monitoring results from scores of samples taken by the Los Angeles Bureau of Sanitation, the Hyperion water treatment plant and the Los Angeles County Sanitation District.

Those samples are tested for total coliform, fecal coliform, and enterococcus bacteria—so-called “indicator” bacteria that signal the presence of agents that can make swimmers sick. The results are compared to state water quality standards and updated each week by the Department of Public Health. Then they are turned into a rolling 30-day online “report card” that grades the water quality at each beach from A to F.

The test results also are shared with Heal the Bay, a nonprofit environmental watchdog group that analyzes water quality at hundreds of beaches along the West Coast and posts its own weekly beach-by-beach assessment, as well as a comprehensive annual report published in May.

Surfrider’s Nelsen compares beach grades to “a spelling class, with a bunch of weekly quizzes.”

“You might get an A or a B or even an F on a given week, but if the scores average out to an A at the end of the month or the end of the year, you’re probably doing pretty well.”

This year’s Heal the Bay report had mixed reviews for L.A. County: Some 82% of the county’s beaches had earned dry-weather grades of A or B last year, a 7-point improvement over the prior year. But the county was still below the statewide average, and trouble spots persisted in places like Avalon and Malibu.

The reasons for those scores tend to defy simplification.

Ken Murray, who directs the Department of Public Health’s Bureau of Environmental Protection, says the test results, and therefore the grades, are impacted by all sorts of factors—weather, water depth, whether the sample was taken near or far from the mouth of a storm drain, even the number of birds in the area.

Pollution control efforts inland can make a big difference. Malibu’s new Legacy Park, for example, is essentially a grassy, state-of-the-art system for capturing urban runoff. And Murray says a new rainwater harvesting system at Penmar Park in Venice “is really going to help the water quality in the beaches because runoff there is going to be captured and treated—and used to water the Penmar Park golf course—before it can hit the bay.”

Precipitation is also a major factor. A beach that is Grade A in dry weather can be rendered unfit overnight by a heavy rain and the ensuing runoff, and be perfectly swimmable again in less than a week as bad bacteria are dispersed by waves and killed by sunshine.

Long Beach, for instance, was a coastal success story this year, partly because of big projects upstream that diverted runoff, upgraded sewers and reduced the tons of debris that the Los Angeles River dumps out onto its beaches. But city officials noted that part of that sharp improvement—93 percent of the city’s beaches recorded A or B grades on the Heal the Bay scorecard—may also have simply stemmed from a relative lack of rain.

Avalon, meanwhile, has been a chronic low scorer and officials have spent years trying to pin down the reasons. “We had thought the problem was sewage lines around Avalon Harbor,” Murray says. “But they spent millions to repair that, and the bacteria levels are still high.”

More tests—these ones on boats—were similarly inconclusive. Now Avalon’s antiquated sewers are undergoing a new, multi-million-dollar round of repairs, and the city is under a cease-and-desist order from the state to clean up its water. Also, Murray says, a team of UC Irvine researchers is studying Avalon “to give us a new set of eyes.”

Amanda Griesbach, a Heal the Bay water quality scientist, says the science is evolving. Someday, she predicts, beachgoers will be able to tell the cleanliness of the water with a single, same-day dipstick test that will be posted at each beach and may even suggest a pollutant’s origin.

“When that happens—and that’s where the science is heading—it will be awesome,” says Griesbach. “But right now, the existing methods are the best we have.”

Posted 6/14/12

Riding to the rescue for 100 years

May 16, 2012

Bathing beauties were still posing on county lifeguard trucks in 1959. Photo/LA County Lifeguard Assn.

Summer isn’t summer in Los Angeles County without the bright yellow vehicles of the beach patrol.

“Iconic” is how Chief Lifeguard Mike Frazer described them last week as the Board of Supervisors gave the Department of Beaches and Harbors authority to sign a proposed agreement to take ownership of the fleet’s latest additions—45 custom-built Ford Escape hybrids that the county has leased since 2008. Under that proposed agreement, Ford Motor Co. would continue to advertise itself as the “Official Vehicle Sponsor” of the L.A. County beach lifeguards. So far, however, Ford has not agreed to a transfer of ownership.

Outfitted with state-of-the-art rescue equipment, the vehicles have saved not only lives but also more than $267,000 a year in fuel costs. “We’ve come a long way,” Chief Frazer says.

In fact, as the photo gallery below shows, beach rescue vehicles have come farther than Southern Californians might imagine. And to look back at their history is to dip into the region’s evolving—and sometimes dangerous—relationship with the beach.

Arthur Verge, an El Camino College history professor and veteran county lifeguard, notes that there was a time, not so long ago, when Southern Californians regarded the ocean as a frightening place that was best admired from afar. “Drownings were sadly common,” Verge says, adding that those who did go into the water often had no idea how to swim or how to get out of the powerful rip-currents that swept them out to sea in their heavy wool bathing outfits.

Professional ocean lifeguards didn’t even exist here until the early 1900s, when the City of Long Beach and real estate developers Abbot Kinney and Henry Huntington began paying “lifesavers” to reassure tourists outside the Long Beach Plunge and to promote the then-new developments of Venice and Redondo Beach.

Notably, Kinney and Huntington turned in 1907 to George Freeth, a celebrated Hawaiian surfer who not only trained L.A. County’s first generation of lifeguards but also pioneered rescue response.

“While fire departments were using horse-drawn rigs,” Verge says, “George Freeth, as early as 1912, was patrolling the beaches of Redondo, Hermosa and Manhattan Beach with a motorcycle, carrying a metallic rescue can in a special sidecar.”

Other early lifeguards were more low-tech.

“Santa Monica’s first lifeguard, ‘Cap’ Watkins, patrolled the beach on horseback,” Verge notes. “And George Wolf, the first Los Angeles city lifeguard, rode back on forth from Venice to El Segundo on a bike.”

By the late 1920s, both the city and county had lifeguards and trucks that ferried their gear along the boardwalks. That gear was stretched thin in the 1930s as the county lifeguards took over the beaches in the economically struggling South Bay.

“We didn’t get any new vehicles until the late ‘40s because World War II was on,” recalls Cal Porter, an 88-year-old retired county lifeguard and Malibu surfer. “If somebody had a bad rescue…we’d jump into this old 1933 International we had and head down Pacific Coast Highway. We’d be going as fast as we could, lights and sirens going—but all the other cars would be passing us.”

With wartime came the 4-wheel-drive jeep, developed by Willys-Overland Motors for the U.S. Army. The Willys allowed lifeguards for the first time to skip the boardwalk and drive directly across the sand. The jeeps were redeployed onto county beaches in the late 1940s; some remained in use for the next twenty years.

By the 1960s, the county had a fleet of Ford trucks with special racks for lifesaving equipment. Beaches filled with Baby Boomers and, occasionally, the products of the era’s experimental mood: In 1970, the county bought two customized dune buggies from the designer Meyers Manx. “But they didn’t work,” Verge says. “Sand would get into the carburetor.”

Lifeguard operations consolidated in the mid-1970s under the county, which by 1975 had the world’s largest lifeguard organization—a distinction that brought marketing opportunities. Among them was the chance for car companies to become the “official” rescue vehicle supplier to the now renowned L.A. County beach lifeguards.

Kerry Silverstrom, chief deputy director of the county Department of Beaches and Harbors, says that in 1986, Nissan and the beach lifeguards signed an agreement. “They got name recognition, ad copy and the ability to say they’re the official vehicle of the County beaches,” she notes, “and we got to use their vehicles for free.”

Nissan’s deal—releasing 30 chrome yellow 4×4 King Cab lifeguard trucks and six light pewter Stanza wagons onto the county beaches—lasted until 1994, when Ford won the contract. Nissan got it back in 1999, but Ford made another comeback with the hybrid SUVs in 2008.

Frazer says lifeguards were accustomed to pickup trucks with gas engines, and concerned that sand might damage hybrids. “But one of our missions is to protect the environment, so we said, ‘Let’s see if this works.’ ”

He says the results have been striking.

“The visibility is amazing and the turning radius is almost twice what we had, so we can navigate crowds better,” he says. “It has traction even in places like Point Dume, which has a steep sloping beach. “

Silverstrom says the relationship with Ford has been a financial and environmental lifesaver as the economy and the Internet have made branding rights a tougher sell at beaches. As for the next generation of vehicles, Frazer says the lifeguards “continue to look at all the options.” After all, only 100 years have passed since George Freeth rode to the rescue on his motorbike.

Posted 5/9/12

A bright idea saves energy—and jobs

April 27, 2012

How many light bulbs does it take to save taxpayers $1.8 million annually and change the course of a layoff?

How many light bulbs does it take to save taxpayers $1.8 million annually and change the course of a layoff?

The answer lies in an innovative new Los Angeles County program that will not only upgrade more than 25,000 lights in county buildings, but also preserve the jobs of nearly a dozen county employees while generating an ongoing source of money for energy efficiency.

The initiative—a revolving fund that will pay in perpetuity for energy retrofitting in county buildings—is the fruit of a $5 million state grant underwritten by federal stimulus money and accepted this month by the Board of Supervisors.

“We’ve been trying for years to set up something like this,” says Tom Tindall, director of the county’s Internal Services Department. He says that, while the county has undertaken hundreds of energy efficiency projects, most have been essentially one-offs, paid for with California Public Utilities Commission grants, departmental savings, specified grants or other one-time revenue sources.

“This will let us do energy projects essentially forever by setting up a fund that will replenish itself,” Tindall says.

For all its conservation, Los Angeles County remains one of California’s most prolific energy consumers.

“Put it this way: We’re Southern California Edison’s biggest customer,” says Howard Choy, general manager of ISD’s Office of Sustainability.

Choy says the county spends well over $150 million a year to power the multitude of office buildings, hospitals, jails and other facilities that make up its vast holdings. The bill for electricity at the Sheriff’s Department alone is about $20 million a year, he says.

Consequently, even a small improvement in efficiency can yield big savings, which is why Tindall, Choy and others were eager to create an ongoing pool of money for projects that would help lower the county’s utility bills.

Despite the county’s financial straits, the Chief Executive Office had planned to earmark $2.2 million in seed money for the idea out of the general fund for the next fiscal year. Then, this month, the California Energy Commission stepped up. The $5 million grant the county received from the commission is expected to result in more than $18 million in utility savings over the next decade.

Under the plan, county departments will be able to “borrow” from the fund to make their buildings more energy efficient, then channel the utility savings back into it until the project’s initial cost is “repaid.” Staff from internal services will perform the work with existing county employees. Most projects, Choy says, will pay for themselves in two to four years.

“After that, the department itself will get to see the savings every year going forward, plus have a better building, and the fund will be replenished for the next project,” he says.

As a bonus, the fund will salvage the jobs of 11 Internal Services employees whose positions had been slated for termination after the state, which had been paying the county to maintain court buildings, decided to outsource.

“A lot of people out there were sweating bullets,” says Tim Braden, ISD’s general manager for facilities operations. “We haven’t been specific by name—we’ve just told them how many people would be potentially impacted—but I’ve got 32 years in this organization and I knew who they were, and know every one of them individually.

“They’re good people, family people, and there’s some who I know would lose their homes if this hadn’t happened. This energy revolving fund is a real lifesaver,” Braden says.

Choy says county department heads will have to sign off on each project, but he anticipates interest will be high. Already, he says, ISD has identified a first phase involving more than 20 county buildings in which a total of $530,000 a year could be saved just by swapping out older, 32-watt fluorescent bulbs for high-efficiency, 28-watt fluorescents.

Potential sites would include LA County+USC Medical Center and its ancillary buildings ($58,197 in potential annual savings), Twin Towers Jail ($44,067), the Hall of Administration ($37,306) and 19 other buildings. An additional pilot project, Choy says, would replace the old, dim, fluorescent lights at ISD headquarters and the county’s Lot 10 on North Broadway with 5,000 bright, energy-saving LED lamps.

A second phase of fluorescent bulb swaps, Choy adds, would yield an additional $500,000 in annual savings. And a separate round of “building tune-ups” aimed at maximizing the efficiency of air conditioning, heating and other energy equipment in a dozen buildings could shave as much as $1.2 million more from the county’s annual spending.

“Every way you look at it,” Choy says, “it’s a win-win.”

Posted 4/27/12

L.A. Earth Day times four

April 19, 2012

Maybe this is the year to experience Earth Day, Topanga-style. The 2011 festivities are shown above.

Sure, you could slap a “Love Your Mother” bumper sticker on your car and call it an Earth Day, but why stop there, when there are so many hands-on ways to mark the occasion?

Whether you fancy yourself an artist, activist, environmentalist or any combination thereof, there’s probably something to suit you in Los Angeles County this Earth Day, Sunday, April 22.

Here are four very different ways to nourish the planet—and the soul:

Heal the Bay

Stewardship will be rewarded during Heal the Bay’s Earth Day festivities. Those who participate in a “Nothin’ but Sand Beach Cleanup” (Option 1 | Option 2 | Option 3) will get free admission to a weekend of festivities at the Santa Monica Pier Aquarium (Day 1 | Day 2). If none of those fit your schedule, you could always make your way out later in the month for the Great L.A. River Cleanup.

LACMA

Earth Day at LACMA: Because Earth without Art is Just “Eh” compiles a heap of Earth-friendly activities with an artistic angle. Visitors can tour gardens and landscape installations, create art from recycled materials, watch films on the benefits of bike culture, and more.

L.A. Works

Service-oriented earthlings might consider joining the folks at L.A. Works for a week of environmentally friendly volunteer opportunities. Build gardens for local schools, or, at the end of the week, participate in Community Day, which commemorates the 20th anniversary of the 1992 Los Angeles riots by building a community garden on a vacant lot where a corner store was burned. The garden will be used to teach local youth about healthy food and will also serve as a park.

Topanga Canyon

If you really can’t decide what you want to do this Earth Day, why not do everything? Topanga Earth Day has it all, over the course of 48 hours. There will be live musical performances, guest speakers, yoga, organic food, native planting, workshops, children’s activities and much, much more. Plus, you’ll get to spend some time in one of the most beautiful natural communities around—on this planet or any other.

L.A. Works volunteers remove graffiti and old fencing to build a community garden for Earth Day 2011.

Posted 4/19/12

A park’s legacy grows in Malibu

February 27, 2012

Legacy Park in Malibu has wildlife, sculptures, outdoor classrooms and five coastal habitats. But to understand why Los Angeles County’s most innovative new recreational area recently racked up its sixth award in 16 months of existence, you have to look deeper—underground, in fact.

Beneath its meandering walkways and drought-tolerant plantings, the 15-acre central park at Cross Creek Road and Pacific Coast Highway is actually a state-of-the-art system for capturing and cleaning urban runoff that would otherwise course to the ocean, carrying bacteria and trash.

Hidden pipes and filters, working in tandem with the park’s landscaping and Malibu’s existing storm water treatment facility, have trapped and decontaminated tens of millions of gallons of toxic storm water since the park opened in October, 2010.

“It’s pretty unique,” says Malibu City Manager Jim Thorsen, noting that the park was just named the American Society of Civil Engineers’ 2011 Project of the Year for California—the latest in a long string of accolades.

“I don’t know of any other places that not only capture and treat their storm water, but then build a park around it and make it possible for visitors to come in and learn.”

The park grew out of longstanding concerns about bacterial contamination from runoff at Malibu Creek, Malibu Lagoon and Surfrider Beach. When winter storms strike in Southern California, the rains carry chemicals and debris into the Santa Monica Bay from as far away as Thousand Oaks and the Santa Monica Mountains, poisoning the ocean and polluting the beach.

Under pressure to comply with clean water mandates, the city bought a vacant lot and—with $13 million in funding amassed from private and public donors, including $700,000 in Proposition A park funds—began turning the dusty tract into what Thorsen has dubbed “an environmental cleaning machine.”

Runoff from some 337 surrounding acres flows into the park via three major storm drains, then is filtered through a system of screens to catch plastic bags, paper cups and other litter. Then the water runs through more filters to a 2.6 million gallon retention pond at the park’s center, where it sits while contaminants settle at the bottom of a natural sedimentation basin.

Finally, the water is piped to the other side of Civic Center Way, where the city’s storm water treatment facility can clean and disinfect it with ozone. Then the cleaned water is used to irrigate the park, or, on rare occasions, is discharged back into Malibu Creek.

“What has really surprised us is how well it has functioned,” says Thorsen. “We’ve seen water go in, the pond fill, the pumps and the system work to perfection, and the water recycle back into the park. It has worked out exactly as it was supposed to work.”

Kathy Haynes, who chaired the ASCE awards committee, calls the park “an innovative example of incorporating sustainability, showing environmental responsibility and using forward thinking.”

For Thorsen, however, the reward is in the number of calls he’s been getting from developers and communities interested in similar projects, and in the public response over the past year as Legacy Park has come to life.

“It looked like a barren desert, when we first planted it,” he says, “but everyone—the people, the birds, the animals—seems to love it. I’m amazed at how much things have grown in just one year.”

Posted 2/6/12

Want to be part of the solution? Some expert tips on how you can avoid contributing to urban runoff are here.

Embracing the dark side in rural L.A.

January 24, 2012

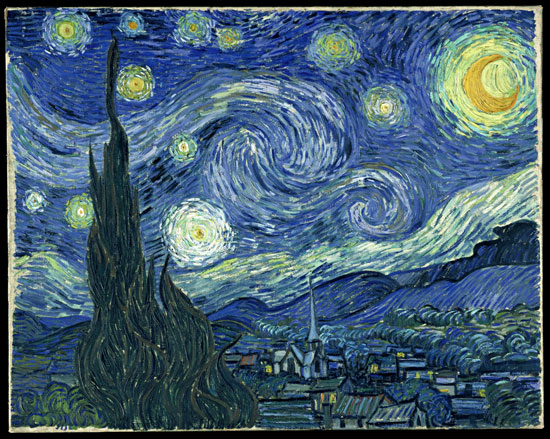

The county's new "dark skies" law may not lead to this kind of view, but it's certainly a step forward.

“Light blight.”

That’s Kim Lamorie’s term for the spectacle that occurs every time an urbanite moves to one of the rural communities near her Calabasas home. The sun sets, the black night settles over the Santa Monica Mountains, and before long, “their houses and yards are massively lit up like crazy,” says Lamorie, president of the Las Virgenes Homeowners Federation.

“It’s how you can tell when somebody’s new to the rural area.”

Eventually, she says, the newcomers come to realize that they don’t need all that security lighting and that bright lights confuse and even threaten the nocturnal animals that share their wilderness. But in the meantime, she says, all that fear of the dark can ruin one of the best aspects of mountain living:

“I can step outside my door at night,” she says, “and see the stars.”

On Tuesday, after more than a year of preparation, the Board of Supervisors restricted outdoor lights in rural Los Angeles County in an attempt to curb light pollution in such unincorporated areas as the Antelope and Santa Clarita valleys and the Santa Monica Mountains.

The new regulations create a Rural Outdoor Lighting District that encompasses those and other sparsely populated parts of the county and requires that lights on barns, corrals, ball fields and other such facilities be shielded so that they face downward, not outward and upward. It also requires outdoor lights, such as those on patios, be subdued enough so that they don’t “trespass” onto neighboring properties.

Although a handful of public safety facilities, such as those operated by the Sheriff and Probation departments, will be exempt from the restrictions, most rural landowners—including the county—must comply with the requirements. That mandate was stressed in a motion by Supervisors Zev Yaroslavsky and Michael D. Antonovich after the Department of Public Works issued rough, last-minute estimates indicating that the cost of replacing lights on the agency’s rural buildings would be so high that would be so high that they would have to dip into funds otherwise reserved for road projects.

“The Department of Public Works should find cost effective ways to comply with the ordinance like every other stakeholder, and they should do so out of their existing . . . budget,” Yaroslavsky and Antonovich said in their motion, calling the estimates “not credible.”

The new rules give county departments six months to report back on how they’ll comply. Homeowners will also get an initial grace period, after which enforcement will be based on complaints. For commercial and recreational facilities, such as ball fields and businesses, lights must be turned off either an hour after a game’s end, at the close of business or at 10 p.m., whichever is the latest.

Rural homeowners applauded the ordinance, championed by Antonovich and Yaroslavsky.

“Out here in the country, most people want to see the stars. And if your neighbor’s got tons of lights, and they don’t shut them off, it really does cause a problem,” said Wayne Argo, who lives in the Antelope Valley on three acres near the Angeles National Forestand who is director of the Association of Rural Town Councils.

“A couple of years ago, we had problems in Leona Valley with people using arena lights on their horse property and not turning them off at a reasonable time,” he said. “For the people in the area, it was like having a baseball field or a football field next door.”

As civilization has encroached on once-unspoiled horizons, city lights have eclipsed more and more of the night sky. Already, astronomers say, the Milky Way has become invisible in two-thirds of the country; after the 1994 Northridge earthquake, the Griffith Park Observatory reports, frightened Angelenos called when the power went out, wondering what the weird, silvery shimmer was in the night sky.

“Some thought it was the end of the world,” according to the observatory’s website. “It was, in fact, the stars.”

Some of the first calls for a curb on light pollution came from stargazers in Arizona. The city of Flagstaff passed one of the first anti-light pollution ordinances in 1958 to stop searchlights from impairing the work of astronomers at Lowell Observatory, where Pluto had been discovered. Then, in 1972, the city of Tucson began requiring city lights to be pointed downward to protect the Kitt Peak National Observatory.

By the mid-1980s, a state statute had been enacted in Arizona, and in 1988, astronomers in Tucsonfounded the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) to advocate on the issue. The IDA now has 58 chapters in 16 countries, helping draft model light pollution ordinances for communities.

In California, the city of San Joseswitched to low-pressure sodium lights in the 1980s to protect the nearby Lick Observatory; San Diego used regulations to dim the skies for the Palomar and Mount Laguna observatories as well.

In recent years, however, the dark skies movement has moved beyond astronomy to touch on environmental, health and lifestyle questions. The loss of darkness has, for example, also affected the feeding, mating and migration habits of wildlife from bats to sea turtles. Meanwhile, medical researchers have uncovered links between the incidence of breast and prostate cancer and exposure to artificial light at night.

In 2002, the city of Calabasas, which abuts the unincorporated Santa Monica Mountains, passed its own local light pollution ordinance, largely to preserve the rural character and local ecology of the community. According to a recent issue of the Las Virgenes Homeowner’s Association newsletter, in the last four years, the city has fielded only about nine complaints of light trespass, all involving commercial night lighting.

Both Lamorie and Argo hope further public education also will be a big part of the county’s light enforcement. And for those who are still not convinced of the new law’s value, Argo has a suggestion.

“You wait ‘til a half-hour or so after sunset, then sit down in a lawn chair, and lay your head back, and look straight up,” Argo said. “You can see satellites. You can see all the constellations. On a clear night, you can almost reach up and touch the Milky Way.”

Posted 1/24/12

Steering clear of bad fertilizer

November 16, 2011

Ah, November. The days are shorter, the light is sharper, and if you breathe deeply, you can almost smell the—whew! Maybe let’s not smell the air today.

Ah, November. The days are shorter, the light is sharper, and if you breathe deeply, you can almost smell the—whew! Maybe let’s not smell the air today.

Yes, fall is fertilizer season in Southern California. And as the autumn air grows pungent over the lawns of Los Angeles County, homeowners are being reminded to spread the wealth responsibly.

“The same nutrients that make your grass grow also will make algal blooms grow if they wash down the storm drains and into the waterways,” notes Susie Santilena, an environmental engineer in water quality at Heal the Bay.

The nitrogen and phosphorus that are so good for plants may contribute to toxic red tides in the ocean and can make algae run wild in freshwater areas like Malibu Creek, creating dead zones as the green scum blocks sunlight and inhibits the growth of other plants and animals, Santilena says.

The algae even wreaks havoc when it dies, because it sucks oxygen out of the water as it decomposes, a process known as eutrophication.

“When you don’t have oxygen in your waterway, your marine life suffocates and you get fish die-offs because there’s no dissolved oxygen in your water,” she says. “And there are aesthetic issues—algae growth can create pond scum, which is just kind of gross to look at in waterways.”

So what to do? It’s tricky, environmental advocates say, because while organic fertilizers such as steer manure and worm castings have advantages that chemical fertilizers don’t share, both can create destructive runoff if they aren’t applied carefully.

Manure tends to adhere to the soil better, so its runoff is less concentrated, but it also can introduce harmful bacteria into the water.

“I have a personal preference for worm castings for multiple other benefits, including environmental impact of production, but they can be overused like the other fertilizers,” says Santilena, noting that worm castings also can be hard to obtain in sufficient quantities for large-scale application.

“It’s how and when the fertilizer is applied that matters most.”

Environmental consultant and master gardener Curtis Thomsen, who conducts the Countywide Smart Gardening program, recommends a half-and-half mix of compost and fertilizer, sprinkled lightly over a lawn that has been aerated.

If you don’t have compost, he adds, there are sites in Los Angeles that offer free mulch that you can shred to make some and low-cost bins can be purchased at Smart Gardening workshops countywide. “The worms smell the organics in it and pull them down, which allows water to penetrate deeper,” he says, adding that compost is especially good for getting nutrients to the roots of thick grasses that tend to thatch. Also, he says, if you add that mixture to your garden plot this fall, it will improve yields, reduce disease in the soil and produce healthier, stronger plants next year.

Meanwhile, Rudy Valenzuela, regional grounds maintenance supervisor for the county Department of Parks and Recreation, notes that the county aerates and fertilizes its park lawns with a commercial chemical blend of nitrogen, potassium and iron that is geared to its sturdy mixture of grasses. He notes, however, that the crews wait until after dark to water and then do it judiciously, turning off the sprinklers after about 15 minutes per station to avoid runoff.

Both approaches keep in mind the need to keep your fertilizer on your own grass. Here are some dos and don’ts from Heal the Bay:

– Do use fertilizer as sparingly as possible, no matter what type you use. Less is more.

– Don’t ever apply fertilizer right before a rainstorm, and never overwater after applying. Too much water will just lift your fertilizer and wash it off.

–Don’t apply to highly compacted or steeply sloped grasses, which also prevent fertilizers from fully soaking into the soil.

–Do consider creating a rain garden, using rain barrels and other containers that will keep rain in your hard and out of the street.

Posted 11/16/11

405 bridge work causes a stink

405 bridge work causes a stink