Spotlight Story

Eight ways to a happier 2012

January 10, 2012

What’s your New Year’s resolution?

Chances are, it’s aimed at a happier 2012. But what works when it comes to improving your day-to-day satisfaction? Can one resolution actually make any difference?

Sure, says Dr. William Arroyo, the Department of Mental Health’s regional medical director. But it may not be the sort of resolution most people are used to making. Here are his tips for a more soul-satisfying year:

1. Resolve to do a self-inventory. “Take note of all the good things, large and small, that were achieved in the prior year,” Dr. Arroyo says. Write them down—you might be pleasantly surprised at all you’ve accomplished. Now take special note of anything that was not only good for you, but also good for your family, workplace or community, and consider doing them again this year.

2. Resolve to give yourself permission to change. This is harder for some people than it sounds, Dr. Arroyo says. Behaviors become entrenched. Friends and families become invested in old habits. “It isn’t always easy to remember that it’s in our nature to pursue good,” he says. “It’s okay to do something differently, especially when doing it the same old way hasn’t worked or has offended those close to you.”

3. Resolve to build pleasure into even into the smallest of budgets. “Maybe you want to manage your money more efficiently,” says Dr. Arroyo, “or allocate for all your bills. That’s fine, but if there’s anything leftover, don’t forget to allocate some resources for pleasure—and pleasure doesn’t have to be expensive. Sometimes pleasure can be just spending time with friends and family, or with those one didn’t have time for in the prior year.”

4. Resolve to be healthy. “And that includes mental health,” the doctor says. “Pay attention to diet and exercise. Avoid harmful substances, whether it’s fatty food, or alcohol or some other potentially harmful thing. But also monitor moods and feelings. If one’s social life is unsatisfactory, think about bringing parts of that to a close. If people around you appear to jeopardize your well-being, think about changing your social circle. Whether it’s foods and beverages or people, give yourself permission to get away from toxic environments.”

5. Resolve to seek peace. “Yoga, prayer, meditation—these work wonders for many people,” says Arroyo. So, he adds, does professional counseling. “Everyone experiences worry and anxiety, but if that’s your primary mood, then it’s probably excessive and you might want to consult with a spouse, a partner, a trusted relative or member of your congregation, or you may want to seek professional help. A little bit of anxiety is normal and useful, but not to the degree where it interferes with your well-being.”

6. Resolve to communicate. “Becoming closer often entails making an inquiry,” says the doctor. If you’d like to be closer to your loved ones, “ask how you can be better with them this year. Be humble. Give the other person permission to let you know when you do something that causes them displeasure—and be willing to change it.” Or, if you aren’t getting what you need from your relationships, resolve to say so: “It’s okay to set limits with others, no matter how close or how distant they might be.”

7. Resolve not to overlook the positive. “One needs to be objective in tough times,” says Dr. Arroyo, “and to keep in mind that there is always more than one way of looking at things. Even in our darkest, most painful moments, there is often a bright side.” Hard times pass, he says, but those who weather them can come away with valuable life experience.

8. Resolve to reach out. “As folks are winding up the year, there’s always a lot of hustle and bustle, and we forget that some people are not as fortunate as we are,” Dr. Arroyo says. “Those who don’t have our means or our health or our rich circle of family and friends could benefit from some demonstration of interest in their well-being—spending time with them, conveying that we care.” Donating to charity isn’t the only route, either. “You can volunteer in an organization,” he says, “or work within your neighborhood.” The key, he says, is to connect and be useful: “It reminds that one is more than the things and money one has.”

Posted 12/30/11

Santa Monica Mountains man on the move

December 14, 2011

On the big screen, Woody Smeck introduces a sneak preview of Ken Burns' National Parks documentary series.

Woody Smeck may speak softly, but he carries a big reputation.

With his wide-brimmed hat and low-key eloquence, Smeck has become the public face of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area and in many ways its staunchest guardian.

As superintendent of the country’s largest urban national park for more than a decade, Smeck has presided over the recreation area as it added thousands of acres of new public open space. Working with partners from every level of government as well as those from community and non-profit groups, Smeck has helped shape everything from firefighting practices to educational outreach to preservation guidelines for sensitive wildlife habitats.

And he has been a tireless advocate for the 153,750-acre recreation area, appearing in this video and countless other forums to explain the complexity and importance of the vast natural preserve at the edge of the one of the world’s largest cities.

Now he’s getting ready to to make his mark on another national treasure. In April, he will become Yosemite National Park’s new deputy superintendent. And those who’ve walked the path with him here are already feeling the loss.

“I’m so sad,” said Kim Lamorie, president of the Las Virgenes Homeowners Federation, which honored Smeck with its “Citizen of the Year” award in May.

“There is only one Woody Smeck.”

In honoring Smeck, Lamorie credited his “quiet but persuasive ability to finesse funding” of new open space acquisitions. Future generations, she said, will “revel in the wonder of the wild and wonderful resources you have preserved.”

Geoffrey Given, who heads the advisory board for the Santa Monica Mountains campus of the educational program NatureBridge, said Smeck’s impending departure is “a huge loss for Santa Monica [but] a huge gain for Yosemite.”

“He has been an unbelievable advocate and supporter of what we do,” Given said. “At all of our fundraising events, he’d show up in uniform with his flat-brimmed hat on.” Smeck also put his money where his hat was, backing the organization’s educational outreach with funds from his own agency’s budget, Given said.

“I think he has made historic contributions to the National Recreation Area,” added Joe Edmiston, who as executive director of the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy has worked closely with Smeck for years. “His shoes will be very difficult to fill.”

In announcing the appointment, Yosemite Superintendent Don Neubacher said Smeck “has the ideal background to helpYosemite achieve unequalled operational and innovative excellence.”

Smeck said Neubacher first reached out to him about joining the Yosemite team about 1½ years ago. With his youngest daughter still in high school, the timing wasn’t right initially. But now that she’s graduating at the end of this school year, Smeck decided to accept the offer.

He’ll head to Yosemite solo in early April and will live in park service housing until his wife, Karen, can join him, probably in July. They plan to buy a home in Mariposa.

The new position could put Smeck in line for greater executive responsibilities down the line—either at another national park or in Washington, D.C.

But he said he’ll miss his Santa Monica Mountains stomping grounds, where he got his professional start in 1991 as a young landscape architect with degrees from Cal Poly Pomona. Smeck reached the recreation area’s top job in 2001. He still marvels that he was able to get there without first transferring to other points around the National Parks system.

“People told me not to expect to stay [in one location] very long,” said Smeck, now 49.

But stay he did—long enough to rub shoulders with influential people ranging from TV documentarian Ken Burns to President George W. Bush.

Bush’s visit in 2003, he said, was a high point—a recognition of the power of collaborative work toward a common goal.

“It was a great opportunity to talk to him about how partnerships work, how cooperative management works, and he genuinely listened to what I had to say,” Smeck said, recalling a 45-minute hike into the Rancho Sierra Vista area of Point Mugu State Park with Bush and a small group that included Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky. “To get a presidential visit…was very uplifting for everyone.”

He said he’s also proud of completing a general management plan that “provides a unifying framework for preservation and stewardship” of parklands going forward. That plan, created with various state partners and the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, established a “cooperative vision” that has informed an array of other actions, including blueprints for fire management and land protection.

His career is a natural outgrowth of an outdoorsy childhood in California’s Central Valley. “I spent my summers hiking and camping in the Sierra Nevada Mountains—especially Sequoia National Park,” he said. “By the time I was 21, I had experienced most of the Sierra Nevada wilderness.”

His first day on the job in the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area started inauspiciously when he got lost trying to find the Rancho Sierra Vista trailhead.

“Back then, you had to drive through residential areas and gravel roads to find the obscure parking lot,” he said. “One of my first assignments was to develop a new entry road and trailhead from Potrero Highway. Today, I’m happy to report that visitors have a very scenic entry drive and wonderful staging area with good signs, drinking water, and clean restrooms to start their park experience at Rancho Sierra Vista.”

As he prepares to venture north to the world-renowned glories of Yosemite’s Half Dome and Bridalveil Fall, he acknowledged that he’ll miss the lesser-known but equally beloved natural treasures he’ll be leaving behind in the Santa Monica Mountains.

“Oh wow, there are so many incredible places. If I had to pick one, the place that’s the closest manifestation of heaven for me is the Old Boney Trail in Point Mugu State Park,” he said. “It is just such a pristine, wild, raw, natural environment. It’s as if you’ve been transported into another world. It is spectacular.”

For Smeck’s photo of the Old Boney Trail and some of his other favorite sights in the Santa Monica Mountains, check out a gallery of his photos below.

Posted 12/14/2011

Weighing the costs of recovery [updated]

December 7, 2011

During the past 18 months, Los Angeles County public health officials have quietly opened a new—and controversial—front in their battle against the painful and costly cycle of addiction, treatment and relapse.

Under a little known pilot project, some 600 uninsured individuals have received roughly 1,500 injections of the drug Vivitrol, which has shown promising results in reducing cravings while allowing the benefits of traditional recovery to take a stronger hold. The publicly-funded project is said to be the largest of its kind in the nation.

Now the Department of Public Health hopes the Board of Supervisors will, in the coming days, approve a request for $3.4 million to expand the delivery of Vivitrol in an even broader effort to determine whether the $847-per-dose injections improve the odds of long-term sobriety—and can do so at a lower overall cost to the public. [See update below.]

“This breaks new ground for the county,” says John Viernes, director of the Department of Public Health’s Substance Abuse Prevention and Control Division. “Many clients, even on a court order, will leave residential treatment after only a few days because the urge to use is so great. If we can get people into recovery faster and decrease relapses, we can serve more people. The whole cycle changes, both in terms of productivity and quality of life.”

The stakes are high: In Los Angeles County, the economic costs of alcohol-related illnesses, injuries, traffic accidents and crime approach $11 billion annually. The Department of Public Health alone spends more than $200 million on substance abuse and prevention programs each year.

Although the drug’s price also is high, Viernes insists it can be lowered through bulk purchase. “The initial cost is high for any new strategy,” he says.

Vivitrol, an extended-release formulation of the anti-addiction drug naltrexone, was approved for the treatment of alcohol dependency in 2006 by the federal Food and Drug Administration. Injected monthly, Vivitrol has been used for several years in private rehabilitation clinics. Last year, it also was approved to assist opiate users in relapse prevention.

Clinicians say the drug helps clients—particularly those with a family history of alcoholism—stay sober long enough to focus on a course of therapy or 12-step program, which is key because studies have shown that long-term recovery rates improve the longer an alcoholic or drug addict remains in treatment.

It’s not a magic bullet,” says Ken Bachrach, Ph.D., psychologist and clinical director at Tarzana Treatment Centers, one of the providers that has participated in the county pilot program. “I view it more as value-added. But if we can get [clients] past six months, they have a much better chance of staying clean.”

Aside from complaints about its administration (a hip injection), the shot’s most common side effects are occasional nausea, headaches or fatigue. Numerous studies have found that recovering alcoholics who combine Vivitrol with counseling tend to stay sober longer, drink less if they relapse and return more quickly to treatment.

Studies done by two insurance providers—Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield of New Jersey and Aetna Behavioral Health Care—also showed that the drug dramatically reduced the hospitalization, pharmacy and medical costs of treating the alcohol-dependent.

The Horizon study, which examined the medical bills of recovering alcoholics for 30 months after Vivitrol injections, found that alcohol-related hospital costs fell 52 percent, total medical costs fell 34 percent and combined medical and pharmacy costs fell 49 percent. Among those requiring the most care prior to their treatment, Vivitrol injections cut medical costs by some $70,000 per patient a year.

But the drug has been slow to catch on, partly because of the cost of the injections and partly because clinicians and alcohol counselors traditionally have been more accustomed to treating substance dependencies with behavior modification therapy and oral drugs, if they use any medication at all. Also, many substance abuse programs lack the necessary staffing and clinical licenses to administer injections, so the patient often has to go to a doctor’s office each month to get the shot.

Tarzana Treatment Center is among the rehab facilities where the county is testing Vivitrol. Photo/Los Angeles Times

Under the county’s pilot project, the drug has been administered during the past 18 months to uninsured clients in various county-funded recovery programs, ranging from people in court-ordered treatment to homeless indigents, says Viernes.

Those county clients have each received between one and four shots since March 2010 as part of their treatment, Viernes says. So far, he says, both inpatient and outpatient clients who’ve been given at least one dose of the drug have been up to twice as likely to complete treatment as those who have not received injections.

One client, a 45-year-old woman who had endured “over 20 detoxes”, reported that, thanks to Vivitrol, her cravings for alcohol had stopped for the first time since her adolescence. A 52-year-old man, who’d been in and out of 12-step programs since his twenties, reported that after two shots, he could focus on his recovery for the first time—and pass a liquor store without realizing it.

Still, despite such testimonials, UCLA researchers have not been tracking clients long enough to determine the medication’s possible benefits for long-term sobriety. Nor is it clear how long an alcoholic or addict might need the injections. The drug’s manufacturer, Alkermes, recommends 6 months to a year of treatment, although county has tried to maintain a 3-shot limit in its pilot program.

Viernes says most of the county clients required only one or two shots to help them focus better on the other aspects of their treatment. But each case is different. At least one participant cited in a preliminary evaluation of the pilot—a 36-year-old blackout drinker and methamphetamine user with a 20-year habit—was on his fourth injection, possibly because of his dual addiction.

“When they’re done with the Vivitrol, what happens? In the next phase, we’re hoping to find that out,” explains Desiree Crevecoeur-MacPhail of the UCLA Integrated Substance Abuse Programs, which is conducting the evaluation.

“Medically assisted” treatments like the county’s pilot project are part of a relatively recent trend in substance abuse research. While many addicts swear by counseling and 12-step programs, few manage to avoid relapses along the way, and even the best-regarded recovery programs are not immune to this reality.

At the same time, however, counselors familiar with the so-called “psycho-social model” of treatment have been slow to incorporate pharmacology into their 12-step and behavioral therapy programs, either because of a reluctance to treat addicts with more drugs or because of the psychological underpinnings of addiction.

In fact, an earlier attempt to incorporate Vivitrol into county treatment programs three years ago fizzled in part because counselors were skeptical, Viernes says.

“There was an aversion to using medication as a means of recovery,” he says, adding that this attitude has softened as medically assisted treatment has become more common.

“Now that we’ve seen its efficacy,” Viernes says, “we’ve reached a tipping point where the clients are coming to us for the injections.” He says demand has risen so quickly that the county’s supply of the drug is nearly gone.

Public health officials say the Vivitrol project took shape after the drug’s manufacturer offered some free samples to Tarzana Treatment Centers, one of the county’s contracting agencies, in 2008.

At the time, Vivitrol had been on the market for only two years, but substance abuse workers were familiar with the generic form of naltrexone, which has been available in pill form since the mid-1990s. The pills had received mixed reviews because, while they cut cravings, they had to be taken daily and patients who skipped pills often relapsed.

The injections were designed to sidestep that problem by ensuring that a single dose would, at the very least, help the patient go 30 days without cravings.

“Alkermes donated 100 vials to Los Angeles County, and we did a small trial with about 32 patients,” says Jim Sorg, director of admissions at Tarzana Treatment Centers. Over six months, the Centers would later report, 23 moved on to residential treatment and only four quit against medical advice.

From there, Viernes says, the study gradually grew to include more than a dozen treatment providers, who refer clients to larger centers, such as Tarzana, for injections.

Expansion of the pilot, he says, will give the county three more years to find out whether medically assisted treatment will slow the revolving door of substance abuse treatment—and to decide whether it improves enough lives and cuts enough from the long-term costs of alcoholism to justify the public expense.

In the meantime, providers are hopeful.

“It’s not a guarantee,” says Bachrach of Tarzana Treatment Centers. “It’s more as if a doctor said, ‘I have something that’s not going to cure you, but will increase your chances of recovery.’ If we can give some extra help to people with addiction, why shouldn’t we?”

Posted 12/7/11

Updated 12/13/11: The Board of Supervisors agreed on Tuesday to broaden the use of the drug Vivitrol in county substance abuse treatment, but also asked the public health department to report back on both the long-term efficacy of the medication and how to lower its cost to the county.

Acting on Supervisor Yaroslavsky’s motion, the board agreed to three more years of funding at a little more than a million dollars annually for the innovative-but-expensive injections, which reduce cravings so that people addicted to alcohol and opiates can better focus on treatment.

“Simply put, this medication helps people stay in treatment longer, which is critical because studies have shown that long-term recovery rates improve the longer an alcoholic or drug user remains in treatment,” Yaroslavsky said.

But Yaroslavsky also wanted better information on the so-called “medication-assisted therapy” and on ways to reduce the $837-per-dose the county must pay for the drug.

The department was asked to report back in three months on bulk pricing and how to improve the likelihood of Medi-Cal reimbursement, as well as how to potentially incorporate Vivitrol into DUI programs.

A follow-up report in a year was also requested to look at medium- and long-term patient outcomes and to examine ways in which the shots—if they turn out to be worthwhile—might be expanded to high-risk populations, such as clients in drug court, probation programs and jail.

The new kids on campus

December 1, 2011

Throughout his 15 years, Mauricio hasn’t had much to celebrate, not with a turbulent family history that has led to a life of foster care and self-doubt. So when the call came, he couldn’t contain himself. “I was jumping up and down,” recalls the impish teenager.

Throughout his 15 years, Mauricio hasn’t had much to celebrate, not with a turbulent family history that has led to a life of foster care and self-doubt. So when the call came, he couldn’t contain himself. “I was jumping up and down,” recalls the impish teenager.

Mauricio had been informed that he’d been picked to participate in an unprecedented summer experiment on the UCLA campus, one that aims to infuse ambition and confidence into a group of kids who rarely go to college mostly because there’s been no one to help them get there.

Mauricio says he packed his suitcase a full month before the start of the intensive, five-week program and arrived so early on the first day that the former sorority house where he and the others would be living was still empty. “I was just so proud,” he says.

In a sense, however, the occasion represented more of a start than a finish. The students will continue to meet monthly on the Westwood campus and, if sufficient funds can be raised, will return in subsequent summers, along with new crops of recruits that will swell the program’s ranks and someday, hopefully, turn them all into full-fledged college students.

On Friday, that pride was shared by plenty of others—but, most importantly, by the 24 inaugural graduates of the First Star UCLA Guardian Scholars Summer Academy, the first such academic program of its kind for foster kids and others under the jurisdiction of child welfare officials. The youngsters, all of whom will be entering 9th grade, were honored during a commencement ceremony highlighted by one girl’s rousing exclamation: “I’m a Bruin now!”

In a sense, however, the occasion represented more of a start than a finish. The students will continue to meet monthly on the Westwood campus and, if sufficient funds can be raised, will return in subsequent summers, along with new crops of recruits that will swell the program’s ranks and someday, hopefully, turn them all into full-fledged college students. (Click here for a video on the program produced by Supervisor Yaroslavsky’s web staff.)

The program’s supporters say they’re determined to shatter the shameful statistics surrounding foster children, huge numbers of whom end up homeless and incarcerated in the years after their 18th birthdays, when they “age out” of the system. Only a fraction of them—an estimated two percent—continue their educations beyond high school.

“You can argue that college is their best possible ladder to leave behind a bad childhood and make it into a happy adulthood and a productive one that will not be a burden on the state, that will be something of high accomplishment,” says media executive Peter Samuelson, a driving force behind the program through his non-profit group First Star, which joined forces with UCLA and the County of Los Angeles.

“There’s nothing the matter with these children. Not one of them,” he says. “All of these kids can go to college. The issue is that nobody ever told them they could. How dumb is that? Who’s failing here, the kids or the grownups?”

The Summer Academy was designed to jump-start the participants’ collegiate careers and expose them to the rigors and culture of university life at a crucial juncture, just as they’re entering high school.

Each earned four college credits through a challenging mix of classes tailored to their educational, psychological and recreational needs. Those included math, literacy, social media, tai chi, cooking and life skills, where they learned meditation and conflict resolution. In the evenings, they were visited by an impressive series of speakers, including National Hockey League great Luc Robitaille, whose Echoes of Hope charity targets the needs of at-risk Los Angeles foster youth.

Each earned four college credits through a challenging mix of classes tailored to their educational, psychological and recreational needs. Those included math, literacy, social media, tai chi, cooking and life skills, where they learned meditation and conflict resolution. In the evenings, they were visited by an impressive series of speakers, including National Hockey League great Luc Robitaille, whose Echoes of Hope charity targets the needs of at-risk Los Angeles foster youth.

And then there were the field trips to, among other places, Disneyland, Skid Row and celebrity Chef Mario Batali’s restaurant, Mozza, where one teenage girl sheepishly confessed to eating nine slices of the establishment’s famed pizza. (The Batali Foundation also contributed money to the Summer Academy, along with the Stuart Foundation, College Board, Sage Publications and Hasbro Children’s Foundation.)

“It scares you in the right way,” Tiffany, 14, says of the program’s morning-to-night regimen. “You know what you’re being pushed to do. A lot of people say, ‘Oh, I want to go to college.’ But until you actually see college kids and what they do and their level of intelligence, it’s hard to say yes.”

Initially, 30 students were selected for the program. But six boys were sent home in the second week for bad behavior, a wrenching decision for all involved. Still, academy officials had no intention of joining the long line of adults who’ve abandoned or given up on such boundary-pushing kids, a reflection of the program’s commitment to—and understanding of—its charges.

Program leaders have remained in contact with the remorseful teens and have held out the promise that they can participate in the group’s monthly UCLA gatherings and, if all goes well at home and in school, they’ll be able to join next summer’s class of young scholars.

“They’ve been told, ‘You are fine young men.’ They’ve all been given hope and a shining pathway of behavior to get themselves back in,” says Samuelson, who raised $305,000 for the summer academy. “When we get these six young men back into the academy, they will count amongst our greatest successes.”

Day to day, the program is run by a seemingly unflappable educator and former vice principal of an elementary school in a tough New Jersey neighborhood. “I fell in love working with students who felt that nobody else cared about them,” says academy director Wally Kappeler, 37, the father of an eight-week-old son.

He says that, for him, the biggest surprise of the summer program was how quickly the kids were willing to open up, especially after an evening session when one of them broke the ice and shared the story of his mom’s death. “Here,” Kappeler says, “they have an opportunity to be heard.”

He says that, for him, the biggest surprise of the summer program was how quickly the kids were willing to open up, especially after an evening session when one of them broke the ice and shared the story of his mom’s death. “Here,” Kappeler says, “they have an opportunity to be heard.”

Kappeler says another boy, shy and self conscious about his weight, would mostly keep to himself like “an outcast” until he was given a special daily job of locking a rear door at their three-story Hilgard Avenue house after deliveries by the caterer.

“He felt so proud that this was his responsibility that he volunteered for all kinds of jobs,” Kappeler says. “He volunteered to take the trash out to the dumpster and wipe the tables and make Kool-Aid for the entire group. And it became contagious…It’s amazing the inspiration that he’s been to us, coming out of his shell and taking a leadership role without saying much of anything at all.”

Because of such breakthroughs and the upbeat bonding between the youngsters, it’s easy to forget the circumstances that brought them to UCLA—the abuse and neglect, the revolving placements in new homes and schools, the philosophies of life that have evolved from the sadness of their situations.

Listen, for example, to Eddie, a soft-spoken 15-year-old, who confides: “Too much happiness could actually hurt you. You just need the right amount because I don’t want to get hurt anymore. Right now I’m not really in the mood for situations like love and happiness. I really want to succeed in my life.” Eddie says he’s determined to be the first in his family to attend college.

Or hear what Thalia, 14, has to say as she speaks for the many who’ve been betrayed by parents. “Even if they’ve done something bad to you, they’re still your blood and they’re part of you and you love them no matter what. And you will always forgive them, even though you’re mad at them at the moment. But they’re always going to be in your heart.”

Kappeler says his heart aches when he hears the kids talk like this. “The emotional baggage they’re holding onto is the stuff that most adults would use as an excuse to give up on life.” Instead, Kappeler says the academy is teaching students to harness the power of their narratives through writing, video and social media so they can become more effective advocates for themselves.

“I want them to feel like they can make a difference in this world just by being who they are and getting their story out,” he says, noting that each was given a laptop and video flip-cam to keep.

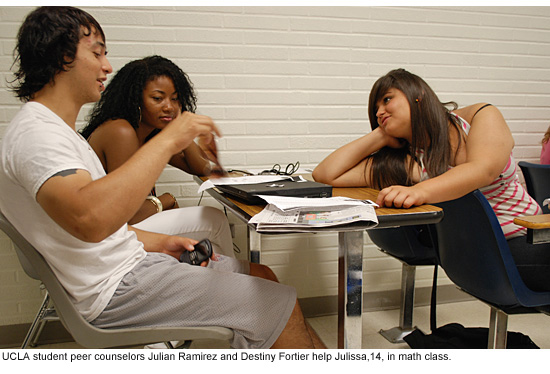

To guide and inspire the participants along the way, the program was staffed by peer counselors and resident assistants who are UCLA students and, for the most part, former foster youths themselves.

One of was senior Julian Ramirez, 21. As a youngster in San Jose, he endured a home fraught with addiction and violence. “One day my dad would say, ‘Let’s go fishing.’ The next, he’d be beating us with the fishing poles.” Under a mop of dark hair, Ramirez says he’s still got a scar from a concrete slab his father smashed against his head. Child welfare authorities, he says, repeatedly removed him and his siblings from his parents.

In his senior year of high school, Ramirez says it was “do or die” and he began to excel, achieving a 4.0 and becoming the captain of the wrestling team. He went to a community college in Cupertino—despite several months of homelessness—and then transferred to UCLA, where he joined the UCLA Bruin Guardian Scholars, a campus association of former foster youth. “What mattered to me most,” he says, “was that I wanted to stay on track with my peers. I didn’t want to be slower than them. And I wanted to prove to myself I was capable.”

In his senior year of high school, Ramirez says it was “do or die” and he began to excel, achieving a 4.0 and becoming the captain of the wrestling team. He went to a community college in Cupertino—despite several months of homelessness—and then transferred to UCLA, where he joined the UCLA Bruin Guardian Scholars, a campus association of former foster youth. “What mattered to me most,” he says, “was that I wanted to stay on track with my peers. I didn’t want to be slower than them. And I wanted to prove to myself I was capable.”

He says he hopes that his empathy and success—and that of the other student staffers—proved useful to the young teenagers in the summer program.

“I’ve been through a lot,” he says. “I know how it is to be 14, angry and not have anyone to talk to.”

In fact, the young participants told UCLA researchers late last week that the student mentors were “really impactful for them,” especially in the way “they talked about their journey through foster care,” says Associate Professor Todd Franke of the School of Public Affairs/Social Welfare, who’s conducting a longitudinal study of the students’ progress.

Franke says that, although it’s too soon to say much definitively about the program, there are some encouraging signs, based on a comparison of initial interviews with the teens and another series conducted on the eve of their commencement.

From the beginning, Franke says, virtually all the students said they wanted to go to college. “But in the past five weeks, the vast majority now see it as a much more realistic goal. It moved them further down the continuum to think that this is a real possibility for them.” They got a sense of the workload, learned that they’d likely be eligible for financial aid and came to believe that they’d have a strong campus support group to help get them through the rough patches, according to Franke. “The process,” he says, “was demystified.”

From the beginning, Franke says, virtually all the students said they wanted to go to college. “But in the past five weeks, the vast majority now see it as a much more realistic goal. It moved them further down the continuum to think that this is a real possibility for them.” They got a sense of the workload, learned that they’d likely be eligible for financial aid and came to believe that they’d have a strong campus support group to help get them through the rough patches, according to Franke. “The process,” he says, “was demystified.”

On Friday, commencement day, an assortment of foster parents, legal guardians and relatives gathered around dozens of tables inside UCLA’s Tom Bradley International Hall. There, they heard speeches about the heart and hope of the young Summer Academy participants. Among the officials who addressed the teens and their caregivers was Los Angeles County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, whose office helped facilitate the program through the Department of Children and Family Services.

He told the teenagers that, on some level, he could identify with their struggles. He said his mother died when he was 10 and that his father worked in the evenings, which meant there was no one to help him with homework or keep an eye on him at night.

“The thing that you have that most college students don’t have is that by the time you get ready to come into college, you probably will have gone through the toughest part of your life,” said the supervisor, a UCLA alumnus. “And while you may not appreciate that, you should embrace that experience, treasure that experience, because it’s going to toughen you up. It’s going to make you tough enough to confront whatever comes along your way, when you’re in college and after that.”

After the speeches were done and the two-dozen scholars received their graduation certificates—along with a standing ovation—it was time for them to leave this place of grownup aspirations and youthful good times. There were lots of hugs and tears, even though they’ll all be together again on campus in a month.

“I feel proud but at the same time I feel sad,” explained Mauricio. “I feel like this is my house.”

Video and photos by Supervisor Yaroslavsky’s web staff.

Posted 8/7/11

Sergeant to the stars calls it quits

November 30, 2011

Sgt. Steve Wheatcroft, escorting Lindsay Lohan into court last year, is no mystery man to those in the know. Photo/AP

The photo captions dub him the “unidentified man,” whether he’s escorting Lindsay Lohan through a blizzard of golden confetti or guiding Mel Gibson through a gauntlet of paparazzi.

But everybody who’s anybody in Los Angeles County courthouse and government circles knows that the tall, broad-shouldered figure in those pictures is Steve Wheatcroft.

The veteran county sheriff’s sergeant has long been an unsung but essential player on the front lines of L.A.’s celebrity-media circus, bringing decorum and safety to the courtroom comings and goings of America’s most photographed.

He’s been responsible for the security of judges like Lance Ito, who presided over O.J. Simpson’s murder trial. He’s made sure that defendants like Lohan, Gibson, Phil Spector and Dr. Conrad Murray made it through media scrums and into courtrooms with a minimum of chaos. And whenever a threat is made against a Los Angeles County judge or member of the Board of

Supervisors, Wheatcroft and his team have jumped into action.

But now, after more than two decades of rubbing shoulders with L.A.’s famous and infamous, Wheatcroft is ready for a little family time.

“As they always say at the Super Bowl, I’m going to Disneyland,” said Wheatcroft, 54, who will retire in the next few weeks after more than 32 years on the job.

Instead of heading up the sheriff’s Security Operations Unit—which assesses threats on public officials, helps manage high-profile trial logistics and provides protection to supervisors and judges—he’ll be hanging with his eight (soon to be nine) grandchildren and cruising around in his black ’59 Corvette.

Leaving the job is kind of like leaving the family business for Wheatcroft, whose brother and son also work for the sheriff’s department.

More than anything, he said, he’ll miss the camaraderie of the eight-member unit that he joined back when it was just a two-man operation run out of the county marshal’s office. When the marshal’s office merged with the Sheriff’s Department in 1994, Wheatcroft’s unit took over protective services for the supervisors as well as the judges. As part of the job, he has served as sergeant-at-arms for the Board of Supervisors’ meetings and helped with logistics for visiting dignitaries ranging from Muhammad Ali to Kirk Douglas.

At Tuesday’s board meeting, the supervisors gave Wheatcroft a big send-off.

“All I can say is this is the sweetest cop you will ever meet,” said Supervisor Gloria Molina. “But that doesn’t take away the kind of commanding presence that he has had here at the board.”

Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky saluted his professionalism and ability to “defuse situations that could have gone the other way,” including threats made against the supervisor or his staff. “You put me and my family at ease during those moments,” Yaroslavsky told Wheatcroft.

Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich thanked Wheatcroft and also singled out his work in the courts. Ticking off a long list of celebrity defendants the sergeant has escorted, he noted: “You could see him in all the movie magazines.”

Which is true, actually, but doesn’t seem to have gone to his head.

Over the years, the “unidentified man” in all those photos has had the chance to observe a lot of famous people under difficult circumstances.

Lohan, Wheatcroft said, is “just kind of a confused girl” who told him she “likes to party.”

Nicest celeb? That would be Rod Stewart, whom Wheatcroft accompanied during a week-long civil proceeding at the courthouse. The British rocker was, in Wheatcroft’s words, “a humble, appreciative person.”

Close followers of the O.J. Simpson case may remember the time the jury, lawyers and judge in the so-called “trial of the century” took a field trip to Simpson’s Rockingham Avenue estate. Wheatcroft arranged it. He did the same with an excursion to Vitello’s restaurant during the Robert Blake case.

And—as if Los Angeles County didn’t have enough of its own well-known defendants—Wheatcroft has been called in to advise officials elsewhere in the U.S.and Canada on how to handle high-profile proceedings. He’s written on the subject in Officer magazine.

By his side throughout has been his high-school sweetheart and now-wife, Wanda. After the board send-off Tuesday, she said her husband had often shared tales from his star-studded work over the years.

“But only in an entertaining way,” she said, “never in a complaining way.”

Posted 11/30/11

Steering clear of bad fertilizer

November 16, 2011

Ah, November. The days are shorter, the light is sharper, and if you breathe deeply, you can almost smell the—whew! Maybe let’s not smell the air today.

Ah, November. The days are shorter, the light is sharper, and if you breathe deeply, you can almost smell the—whew! Maybe let’s not smell the air today.

Yes, fall is fertilizer season in Southern California. And as the autumn air grows pungent over the lawns of Los Angeles County, homeowners are being reminded to spread the wealth responsibly.

“The same nutrients that make your grass grow also will make algal blooms grow if they wash down the storm drains and into the waterways,” notes Susie Santilena, an environmental engineer in water quality at Heal the Bay.

The nitrogen and phosphorus that are so good for plants may contribute to toxic red tides in the ocean and can make algae run wild in freshwater areas like Malibu Creek, creating dead zones as the green scum blocks sunlight and inhibits the growth of other plants and animals, Santilena says.

The algae even wreaks havoc when it dies, because it sucks oxygen out of the water as it decomposes, a process known as eutrophication.

“When you don’t have oxygen in your waterway, your marine life suffocates and you get fish die-offs because there’s no dissolved oxygen in your water,” she says. “And there are aesthetic issues—algae growth can create pond scum, which is just kind of gross to look at in waterways.”

So what to do? It’s tricky, environmental advocates say, because while organic fertilizers such as steer manure and worm castings have advantages that chemical fertilizers don’t share, both can create destructive runoff if they aren’t applied carefully.

Manure tends to adhere to the soil better, so its runoff is less concentrated, but it also can introduce harmful bacteria into the water.

“I have a personal preference for worm castings for multiple other benefits, including environmental impact of production, but they can be overused like the other fertilizers,” says Santilena, noting that worm castings also can be hard to obtain in sufficient quantities for large-scale application.

“It’s how and when the fertilizer is applied that matters most.”

Environmental consultant and master gardener Curtis Thomsen, who conducts the Countywide Smart Gardening program, recommends a half-and-half mix of compost and fertilizer, sprinkled lightly over a lawn that has been aerated.

If you don’t have compost, he adds, there are sites in Los Angeles that offer free mulch that you can shred to make some and low-cost bins can be purchased at Smart Gardening workshops countywide. “The worms smell the organics in it and pull them down, which allows water to penetrate deeper,” he says, adding that compost is especially good for getting nutrients to the roots of thick grasses that tend to thatch. Also, he says, if you add that mixture to your garden plot this fall, it will improve yields, reduce disease in the soil and produce healthier, stronger plants next year.

Meanwhile, Rudy Valenzuela, regional grounds maintenance supervisor for the county Department of Parks and Recreation, notes that the county aerates and fertilizes its park lawns with a commercial chemical blend of nitrogen, potassium and iron that is geared to its sturdy mixture of grasses. He notes, however, that the crews wait until after dark to water and then do it judiciously, turning off the sprinklers after about 15 minutes per station to avoid runoff.

Both approaches keep in mind the need to keep your fertilizer on your own grass. Here are some dos and don’ts from Heal the Bay:

– Do use fertilizer as sparingly as possible, no matter what type you use. Less is more.

– Don’t ever apply fertilizer right before a rainstorm, and never overwater after applying. Too much water will just lift your fertilizer and wash it off.

–Don’t apply to highly compacted or steeply sloped grasses, which also prevent fertilizers from fully soaking into the soil.

–Do consider creating a rain garden, using rain barrels and other containers that will keep rain in your hard and out of the street.

Posted 11/16/11

Catching an early bird Expo Line ride

November 6, 2011

This is only a test—but not for long. As the Exposition Light Rail Line rolls closer to becoming a reality for Los Angeles transit customers, operators are now trying out the trains daily on portions of the new route. (Details on the test runs—from Flower and 23rd Street to La Cienega and Jefferson Boulevard—are here, along with safety tips.)

Supervisor and Metro Board Member Zev Yaroslavsky recently hopped aboard one of the test runs. The view from the train made it clear, he said, that getting from Point A to Point B will be only part of the Expo Line’s journey. As new routes connect with existing lines, entire regions of Los Angeles County are becoming accessible via public transit.

“Every one of these lines is another tipping point,” Yaroslavsky said.

All the test runs are a prelude to opening the first leg of the line early next year. Initially, trains are expected to run from the 7th Street Metro Center downtown to La Cienega and Jefferson. Meanwhile, construction is continuing on Phase 1’s westernmost station in Culver City.

This interactive map provides a preview of some of the cultural attractions, employment centers and educational institutions along Phase 1 of the route—including USC, the Natural History Museum, the California Science Center, the California African-American Museum and the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

Eventually, Expo Phase 2 will extend all the way to 4th Street and Colorado Avenue in Santa Monica. Ground was broken on that phase a couple months ago. When complete, the 15.2-mile line will be the first mass transit rail project on the Westside since the Red Cars.

Posted 11/6/11

Fault findings break new ground

October 21, 2011

Years before the first trains roll, the Westside Subway is already getting somewhere—at least when it comes to seismic discoveries.

Years before the first trains roll, the Westside Subway is already getting somewhere—at least when it comes to seismic discoveries.

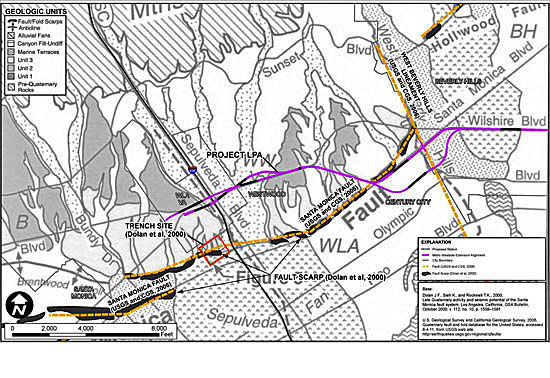

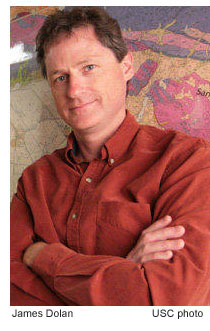

Earthquake geologist James Dolan, a USC earth sciences professor and consultant to the transit project, this week presented findings that pinpoint the location—and active seismic status—of a formation known as the West Beverly Hills Lineament.

Remember that name.

It turns out the WBHL, as it’s known, is a branch of the mighty Newport-Inglewood Fault, an active and powerful system stretching from Culver City to Newport Beach and continuing south through San Diego and into Mexico’s Baja peninsula.

Dolan led the research team that first came across the formation and named it in the early 1990s. But it was only in recent months that intensive research to determine the safest site for the subway’s Century City station helped the geologist “confirm our earlier inferences that the West Beverly Hills Lineament is the northernmost part of the Newport-Inglewood Fault System.”

In the world of seismology, that’s a big deal. The Newport-Inglewood system is a giant and has been active during the Holocene era (i.e., the last 11,000 years), most notably in 1933, when it caused an earthquake in Long Beach that killed some 120 people, making it the second deadliest in California history, after the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906.

The presence of the WBHL and the nearby Santa Monica fault, which is also active, make it too dangerous to build a Santa Monica Boulevardstation for the new subway in Century City, Dolan and other scientists told a Metro committee Wednesday. They said that another proposed location for the station—at Constellation Boulevard and Avenue of the Stars—was a better option because it showed no evidence of earthquake faults.

The state has recognized the WBHL and the Santa Monica Fault as active fault zones on its maps, Dolan said, but does not yet classify them as such under the Alquist-Priolo Earthquake Fault Zoning Act, which imposes building restrictions in such areas. Data like those acquired during the recent research are the kind of information needed to eventually place such active fault zones under Alquist-Priolo regulations, Dolan said.

“As a scientist, it’s very exciting,” said Lucy Jones of the U.S. Geologic Survey and Caltech, who reviewed the research as part of an independent review panel. “Knowing that the Newport-Inglewood Fault is active this far north is new,” she said, later adding that the finding is “of significant import for the city of Los Angeles.”

The WBHL extends north-northwest from Culver City through West L.A., bisecting west Beverly Hills and east Century City, traversing Constellation andSanta Monica boulevards between Moreno Drive and Century Park East before ending roughly at Sunset Boulevard.

A “major event” on the WBHL could mean an earthquake ranging in magnitude from 6.4 to 7.2, along with ground movement of three to six feet, according to an executive summary of the experts’ findings.

While it’s not possible to predict when a given fault might slip, it’s prudent to take the potential impact seriously, Dolan told the committee:

“Earthquakes don’t typically recur on our kind of human lifetime scales,” Dolan said. “That doesn’t mean that we can disregard the risk associated with these things. It very well may be it will be 3,000 years until we have an earthquake on the Santa Monica Fault. Then again, it could happen tomorrow. It depends on whether you’re a betting person, I guess.”

While acknowledging that such discoveries can spark concerns, Dolan said in an interview that he prefers to take an all-news-is-good-news approach.

“I think anything we learn about active faults in L.A.is always good news,” he said, “because it’s absolutely critical that we fully understand the seismic threat facing us as residents of earthquake country.”

Members of the Metro committee listened attentively during Dolan’s presentation (and one, Richard Katz, asked him to slow down at one point so he could take in the rush of information.)

Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, another committee member, said he was so engrossed with Dolan’s style of scientific explanation that it might once have set him on a different career path.

“If I’d first met him 40 years ago, I would have been a geology major,” Yaroslavsky said.

Dolan, an expert on urban faults and the seismic hazards underlying the metropolitan Los Angelesarea, said the latest round of extensive research gave him a chance to catch up with his unfinished business with the WBHL. “These data have been a wonderful validation of our earlier research,” he said. “They’ve greatly fleshed out the details of these faults. Those details are the critical information we need.”

At the committee meeting, he spoke enthusiastically about the exhaustive testing that helped unearth those details, including “cone pentetrometer” tests and “seismic reflection profiles” (“It’s like a CAT scan of the earth,” Dolan explained to the committee.)

After it was all over, the committee chair, Diane DuBois, paid Dolan and the other scientific experts the ultimate layperson’s compliment on their presentation:

“I even understood it,” she said.

Posted 10/20/11

Realignment gets all too real

October 6, 2011

Inside a cramped, dingy-white building in Alhambra, one of California’s most radical—and some say reckless—experiments in its criminal justice history is unfolding. There, officials are getting a detailed first look at some of the thousands of state inmates who’ll be supervised by Los Angeles County once they’re freed, a process that began this week.

Inside a cramped, dingy-white building in Alhambra, one of California’s most radical—and some say reckless—experiments in its criminal justice history is unfolding. There, officials are getting a detailed first look at some of the thousands of state inmates who’ll be supervised by Los Angeles County once they’re freed, a process that began this week.

So far, it’s not an encouraging sight.

Hundreds upon hundreds of prisoner files—some woefully incomplete—are haphazardly arriving by mail, fax and Fed-Ex at Los Angeles County’s “pre-screening” hub in the Probation Department’s Alhambra field office. Eagle-eyed probation workers are uncovering mistakes, large and small, in the state records, including inmates who should be sent to other counties and others whose crimes should disqualify them entirely from the new “realignment” program.

Only late last week, after intense pressure from L.A. County, did state corrections authorities even begin sending comprehensive mental health records on ex-convicts headed here for supervision, information that’s crucial in developing treatment plans for the clients and protection for the public.

What’s also become increasingly clear in recent days is that the state has not been entirely forthcoming about the fine print of the controversial realignment plan, which is aimed at reducing prison overcrowding while slashing the state’s budget deficit.

Again and again, the governor and legislature have publicly stressed that the ex-inmates who’ll be supervised by the counties are “low-level” offenders convicted of non-serious, non-violent, non-sexual crimes. They also note that these individuals would have returned to their home counties no matter who was responsible for their oversight. But that’s not the whole story, as L.A. County officials are quickly learning.

These same felons could—and sometimes do—have prior cases involving very serious crimes. Under the realignment law, AB 109, only the most recent conviction, or “commitment offense,” is considered in determining whether inmates will be supervised by counties or state parole agents after their release.

Take, for example, one inmate who was scheduled to be freed on Wednesday and has been ordered to report to L.A.County for post-release supervision. He was serving time for second-degree commercial burglary, attempted grand theft of personal property, forgery and identity theft—all non-serious, non-violent crimes under the penal code. But over the previous decade, he had more than a dozen arrests or convictions for a slew of serious and violent crimes, including assault with a deadly weapon, robbery and terrorist threats.

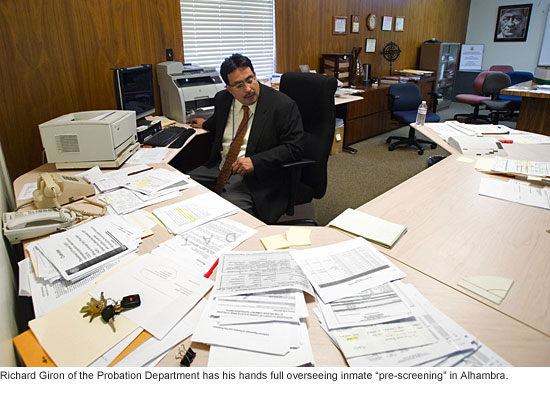

“We’re literally seeing every criminal record you could think of,” says Richard Giron of the Probation Department, who’s in charge of the pre-screening center in Alhambra, where nearly 2,000 files have been received. “We’re seeing prior violence, prior sex offenses—the full range of minimal criminal records to extensive, serious records.”

Giron says his staff is flagging such individuals for heightened supervision as part of the case plans developed when inmates arrive at other hubs throughout the region for face-to-face interviews.

Reaver Bingham, the Probation Department’s deputy chief of adult services and juvenile placement, called some of the county’s new charges “very hard core” but insisted that his agency is trained and prepared to deal with them. “This population is not unfamiliar to us,” he said, noting that the department currently supervises 15,000 adults with histories of serious and violent crimes.

In recent weeks, as AB 109’s October 1 implementation date drew near, concerns about public safety took center stage, with the harshest warnings coming from Los Angeles County District Attorney Steve Cooley. He predicted that crime rates would soar not only because of the freed inmates who’ll be under county supervision but because, under the law, defendants convicted of non-violent, non-serious crimes will now be sentenced to county jail rather than state prison. He and others argue that this will lead to even greater jail overcrowding and more inmates being released early by the Sheriff’s Department, which manages the sprawling system.

In the Alhambra screening center, Giron and his hand-picked team understand the high stakes for public safety and are determined to make sure no inmate is erroneously placed under the county’s jurisdiction. His 11 deputy probation officers and two supervisors scour every document the state sends and then comb criminal databases, as well as court records, for additional information on each of the inmates scheduled for release.

In the process, Giron says, his staff has uncovered mistakes that have given county officials ammunition to keep dozens of inmates from falling under probation’s purview.

“I’m doing everything I can in my power to reject cases that are inappropriate for supervision in L.A. County,” Giron says. Those cases have included an inmate who’d been serving time for molesting a child under the age of 14, a prisoner convicted of a serious extortion attempt and yet another who was described by the state’s own prison board as not safe to be released.

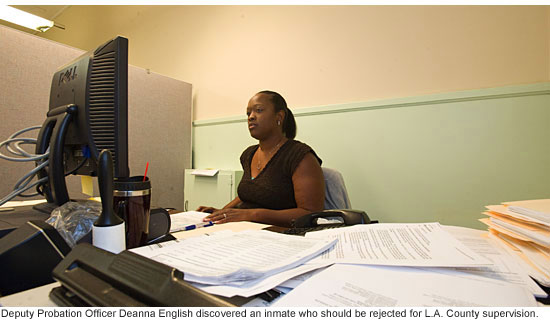

On Wednesday morning, Deputy Probation Officer Deanna English, a 22-year veteran of the department, found yet another, using the scant information contained in the state’s own file as a springboard.

Corrections officials had determined that a 20-year-old inmate at the California Rehabilitation Center in Norco was eligible for county supervision because, according to a release form, he was serving time for a second degree burglary. But that was wrong. Contained within the file itself was the notation that he’d been sentenced for a robbery, a serious crime that would exempt him from the realignment program. English says she then checked the actual court record, which confirmed the robbery conviction.

“Honestly speaking, I thought they were trying to pull one over on us,” she says of corrections officials. “Their thing is to get as many [inmates] out of the state system as they can.” English says she feels “a high sense of duty” to thoroughly vet every file.

Making the job even more challenging for the Alhambra crew is the fact that the state has no centralized point of contact. The county is receiving files from 33 separate prisons. And those files are not being sent based on the chronological release dates of inmates, dates that seem to be constantly shifting.

Just the other day, as Giron talked with a visitor from Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky’s office, another probation supervisor, Al Montellano, walked up with a handful of documents fresh off the fax. They stated that eight inmates scheduled for release on December 4 will now be freed on October 23, meaning that the time-consuming review of their cases will have to be rushed into the mix, putting others on hold.

“That,” Giron says with a hint of understatement, “is operationally inefficient.”

Progress finally has been achieved, however, in one of the most crucial facets of the screening process—determining the mental health status and needs for the estimated 20 percent of inmates coming to the county who’ll need some level of treatment.

For months, the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health, a key player in the realignment process, had been stymied in its efforts to obtain comprehensive treatment records for inmates. The information provided by the state was simply a notation that mental health services had been delivered in prison.

“We were getting promises and assertions that were not true,” says Dr. Marvin Southard, director of mental health. “It was very frustrating.”

Among other things, Southard says his department was directed to dial an information number on the inmate forms. “If you call that number, you get a correctional counselor—the cell-block staff person—but they have no access to the medical records,” Southard says.

Further, according to Southard, his staff was told that they’d have to individually contact each of the state’s 33 prisons for information, which would consume crucial time in learning an inmate’s needs and creating a treatment plan.

The issue reached a boiling point two weeks ago when the Board of Supervisors voted to send a stern letter to Gov. Jerry Brown. In it, they warned that, unless the necessary information was forthcoming, “we will not accept parolees with mental health issues.”

“After that, everything changed,” Southard says, noting that a centralized system was developed by California’s corrections officials. “The governor’s staff promised that we’d get the records we need.”

Still, even if the county manages to overcome all these logistical challenges, there’s still the overarching question of whether the state will provide the money necessary to make it all work today and in the future.

“This has been my concern from Day One,” says Supervisor Yaroslavsky. “We’ve been asked to take a leap of faith that the reimbursement is adequate to meet our responsibilities. You can’t blame us for being skeptical, especially given the problems that have emerged in the opening days of this program. Even though the governor has assured us he will make us whole, it’s not entirely up to him and that makes me nervous.”

Posted 10/6/11

Check for the latest closure information

Check for the latest closure information